In May, controversy over “the ultimate American Bible” briefly rocked the Christian publishing world. Big-name Christian authors penned a letter blasting it as “dangerous,” and more than 900 people signed a petition decrying the decision to print the book. The Bible’s advertised publisher, a part of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, disavowed the book and denied it ever had plans to print it in the first place.

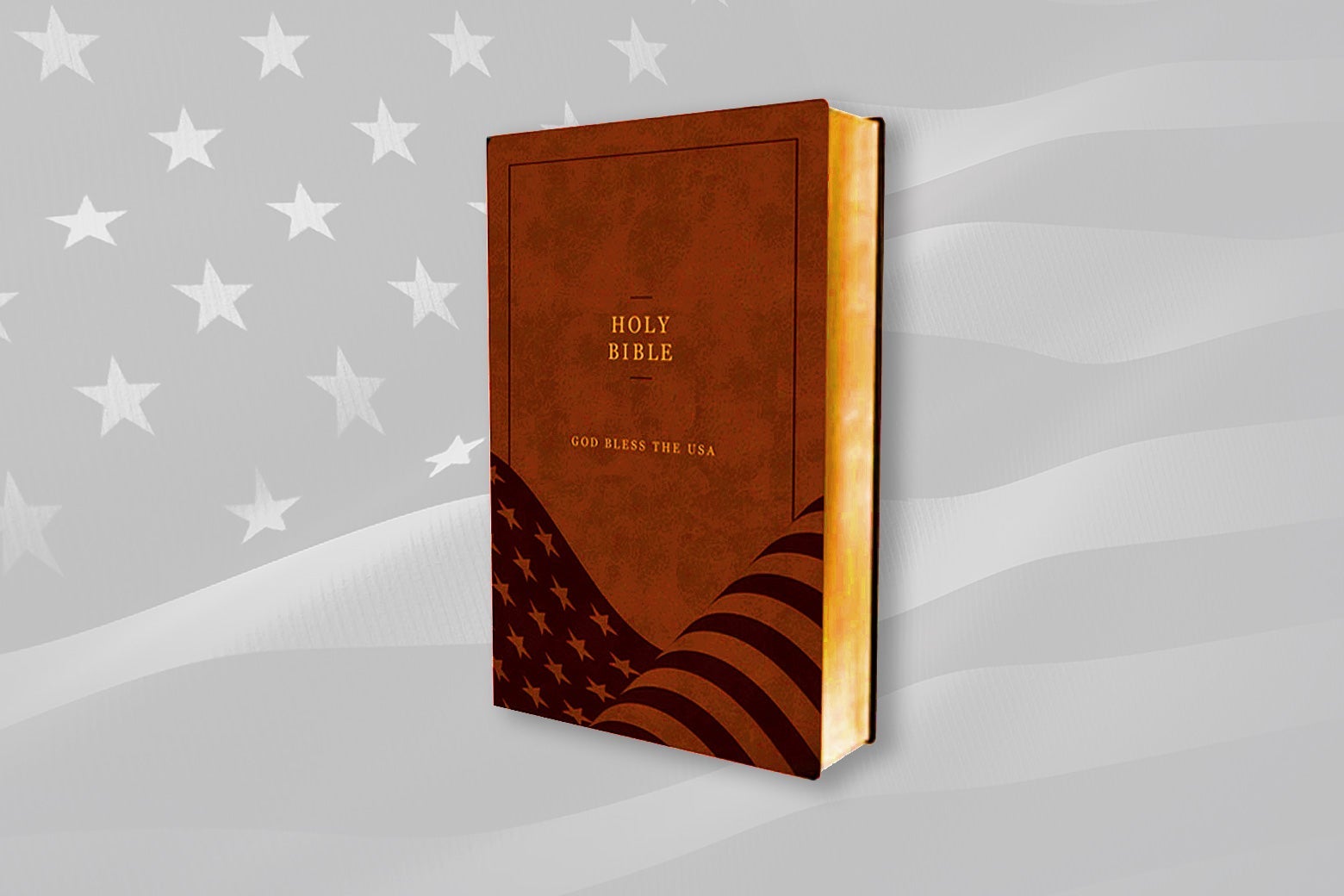

The $60 Bible, which was originally set to ship early this month to commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11, was “inspired by” the country musician Lee Greenwood’s 1980s patriotic anthem “God Bless the USA” and packages Scripture with the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, the Pledge of Allegiance, and the handwritten chorus to Greenwood’s song. The ensuing uproar shows the challenges facing publishers in the lucrative Bible-printing business and the growing discomfort with Christian nationalism, the ideology that asserts the United States should be an explicitly Christian country.

The maker of the God Bless the USA Bible said it was not designed as a Christian nationalist book. Hugh Kirkpatrick, the president of the marketing company behind the Bible’s development, said he wanted to make a “one-stop shop” Bible to encourage Americans—and not just Christians—to learn about the “Judeo-Christian values” that he sees as underpinning the country’s founding. “We built this to be a bridge, not to divide,” he said. “We tried to say, ‘OK, we love freedom, and we all want to be free,’ and this process was to let people understand why the Founding Fathers used the Bible as a guide.” He added that he was not trying to “convert” anyone to his religion or his worldview. “There’s no racism involved, no nationalism involved,” he said.

Kirkpatrick originally claimed he reached an agreement with the evangelical publishing company Zondervan, the division of HarperCollins that owns the rights to the New International Version translation of the Bible, to print 1,000 copies. But many critics, alerted to its existence by reporting from Religion Unplugged, said that no matter Kirkpatrick’s claims, the message was clear. “The implication is the American founding documents were divinely inspired,” said Catherine Brekus, a professor of the history of religion in America at Harvard Divinity School.

A week and a half later, in the face of a public outcry, Zondervan denied its support for the Bible, leaving Kirkpatrick to scramble to find another way to manufacture his text. (Kirkpatrick claimed Zondervan bailed after the petition; Zondervan has said Kirkpatrick had been “premature” in marketing the Bible as an NIV Bible and that the company decided before the outcry began that the Bible was “not a fit.”)

Before the election of President Donald Trump, Kirkpatrick’s Bible may have been received with indifference. Christian nationalism, the fusion of American national identity with white, conservative, Protestant Christianity, had been considered a fairly standard Christian position throughout American history. The ideology began to take on its current culture war connotations in the 1960s, according to Brekus, as large numbers of immigrants arrived and the civil rights and counterculture movements disrupted the status quo. White evangelicals began to see their conceptualization of the U.S. as a Christian nation as under attack. According to John Fea, a historian and the author of Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump, the modern form of Christian nationalism took root in the 1970s, with the rise of Jerry Fallwell’s “Moral Majority.” “Since the late 1970s, this ‘God and country’ thing has been something you fight for, not something that’s a given,” Fea said. “The idea of fusing the Bible with patriotism really took on a culture war sensibility.”

It was around this time that evangelicals began to bring American history into the Bible. After President Dwight Eisenhower died in 1969, the American Bible Society, which first published the Good News Bible, put out an Eisenhower version, which simply had his name on the cover, a single page explaining his love for the Bible, and his photo in the back. “Even then, they were deeply divided about whether they should do this,” Fea said. “They agonized over it.” But there was no turning back. In the 1970s, Brekus said, an evangelical market emerged that made it clear there was demand for religious products. Bibles, as a consumer good, grew increasingly diverse.

Falwell himself kicked off the trend of broadly “patriotic” Bibles with his I Love America Bible in 1983. His Bible, which on its cover featured a portrayal of Revolutionary war soldiers, included biographies of the presidents, an essay on the American revolution, and the text of the U.S. Constitution. Twenty-six years later, the Southern Baptist pastor Richard G. Lee put out The American Patriot’s Bible, which made explicit arguments for the divine inspiration of the country’s founding. The Bible wove illustrations of notable presidents and commentary about Second Amendment rights and individual liberty and the glory of military service in inserts between pages of Scripture. Compared to the explicit messaging and militarism of the American Patriot’s Bible, the Lee Greenwood Bible is remarkably subtle.

The even more conservative Founder’s Bible, the Young American Patriot’s Bible, The American Woman’s Bible, the 1599 Geneva Bible: Patriot’s Edition, and several military Bibles were published in the following years. The purpose of these Bibles, experts say, was to promote the idea of the United States as both a Christian nation and a nation specially favored by God as part of his divine plan, or at least a nation with a divine mandate to spread American and Christian values around the world.

Trump’s election changed how many more progressive evangelicals saw the idea, particularly after the researchers Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead published research highlighting the influence of Christian nationalism and connecting it to support for Trump. According to Whitehead, around half of all American adults are broadly in favor of thinking of America as a Christian nation, and a smaller segment of those Christians—about 20 percent of Americans overall—strongly advocate for the idea. Many faith leaders who noticed the ideology in their churches really began to worry after the Jan. 6 insurrection, when the rioters waved crosses and Christian protest signs. “We can’t unsee the Jesus signs next to Trump signs, the Confederate flag paraded, the broken windows, injured bodies and officers assaulted,” the Zondervan authors wrote in their public letter protesting the God Bless the USA Bible

The population of enthusiastic Christian nationalists has shrunk slightly in recent years, Whitehead said. But the rhetoric has grown more prevalent, and the idea of fighting for “religious freedom” has gained salience in the era of mask and vaccine mandates. “People think about defending Christianity more than they used to,” he said.

So it is not surprising that a publishing company may have considered the Lee Greenwood Bible a potentially fruitful product. Printing the Bible is a very profitable business, and there is a constant demand for it. Christian publishers, then, have to make the case for consumers to choose their particular Bible. To do so, they’ll produce Bibles with additional prayer material, or Bible study questions, or notes about particular translations. At any given moment, shoppers looking for a new Bible can find the standard King James, New International Version, New Revised Standard Version, and English Standard Version translations, to count a few. They can also find Bibles geared toward women and children and scholars and even athletes and businesspeople. “You want to get different bells and whistles that will appeal to certain consumer markets,” Perry said. “I cannot exaggerate the extreme diversity of Bibles out there.”

But Bibles aren’t just utilitarian items; they’re also statements, and Christians will cough up $60 for a Bible with public domain material just to send a message about who they are. The God Bless the USA Bible’s website notes that it would make a great gift for “‘Faith and Values’ advocates” and “anyone that loves America.” “It’s a self-identifying symbol, a status symbol,” Perry said. “It could be they were banking on this kind of God Bless America Bible being purchased as an expression of loyalty to this ‘God and country’ conservative identity. I think publishers were thinking there may be a big enough market of people who would say, this is the kind of declaration I would make with my Bible.”

But publishers also likely knew from the start that the Lee Greenwood Bible had the potential for backlash. Bibles have always been contentious as symbolic statements. When Zondervan was set to release an updated version of the NIV in the mid ‘90s that included more gender inclusive language (an apostle addresses “brothers and sisters,” rather than just “brothers,” for example), evangelicals cried out against the infiltration of feminism and “political correctness” into Bible publishing, causing Zondervan to be “worked over in blogs and in magazines,” according to Perry. Prominent evangelicals told Americans to stop reading the NIV, and Crossway publishing, alongside the National Council of Churches, put out the now-popular English Standard Version in response. (Evangelicals are the primary audience targeted in Bible publishing.) The NIV is still known as a “liberal” Bible in certain circles, Perry said. That experience may have made Zondervan more hesitant to take risks that might damage their reputation, in either conservative or progressive circles.

Zondervan’s rejection of the Lee Greenwood Bible shows that Christian nationalism isn’t as safe a financial bet as it might have been, now that the public is more alert to its potential dangers. According to Brekus, earlier patriotic Bibles were met with opposition in their day: Christianity Today, the flagship evangelical publication, blasted the American Patriot’s Bible as idolatrous when it was published in 2009. Back then, the magazine described such a concept as elevating the U.S. to the point of being worshipped. But still, the Bible was published by Thomas Nelson, HarperCollins’ other major Christian imprint.

But it’s not just a matter of public backlash. Melani McAlister, a professor of American Studies at George Washington University, emphasized that many evangelicals consider Christianity a global faith and are uneasy with the idea of tying it too closely to nationalist ideologies. “Putting the Bible or placing American history within the Bible, or suggesting the U.S. is a source of revelation, is seen by many evangelicals as a kind of heresy,” Brekus said. For some segments of the potential customer base, the issue is not Christian nationalism but the idea of soiling a sacred object by printing Scripture with anything else.

It’s hard to know whether Zondervan’s rejection of the Lee Greenwood Bible will actually damage its sales. While Kirkpatrick will no longer be able to print with the NIV translation—the best-selling Bible out there—he said he has found other printers and companies that will use the historic, public domain version of the King James Bible. The first 3,000 will now ship in mid-October because of labor shortages and supply-chain issues, he said. That’s a small number, but Kirkpatrick said that the “custom, unique” nature of the product has limited what he can produce, and that he is currently just testing out the market, anyway. He has sold 5,000 Bibles in pre-sale and expects to sell many more once he begins a marketing campaign. Kirkpatrick said he was pleased with the demand for the Bible and that the public backlash didn’t worry him. “I think for the people that wanted this product, that helped us,” he said. “For the people that weren’t going to buy the product anyway, it didn’t do any damage.”

Ultimately, Perry believes that most Christians are likely aware of what this Bible is trying to do. “People aren’t dumb and can recognize that this is a kitschy and goofy ‘God and country’ money grab,” he said. “Or a naked appeal to partisan culture wars.” The earlier and more overtly nationalist American Patriot’s Bible sold well, but only with “a particular market that’s itching for culture war content.” The issue with the Lee Greenwood Bible, he said, is that it was aiming for a niche market that, at least for a company concerned with public opinion, wasn’t big enough to be worth the reputational damage.

Is there an interesting story happening in your religious community? Email tips to molly.olmstead@slate.com.