Seeking a basis for reconciliation between Jews and Christians has been a much-pursued enterprise over the past few centuries. For the most part, the quest has been founded upon a mutual willingness to dilute religious conviction or bracket it altogether. In his stimulating essay on Christian Zionism, Wilfred M. McClay, one of the most perceptive observers of American culture, describes a new way forward for Jewish-Christian relations, one found among “people who have serious and unwavering commitments to their respective faiths and are not interested in coming together merely for the sake of achieving a lowest common denominator.”

To be sure, McClay acknowledges that the emerging relationship is “fragile and tentative” and that it is regarded with suspicion by many, and perhaps the majority, of the most committed members of each community. Still, its increasing importance cannot be gainsaid, for it is an experiment that tests a proposition of the utmost importance to the believers of each tradition. Can the “commonality of Christians and Jews,” McClay asks, be founded upon “something that does not require either group to mute its differences or soften its commitments to the distinctives of its faith by resorting to the kind of ‘interfaith dialogue’ that is made possible only by the feather-lightness of those same commitments?”

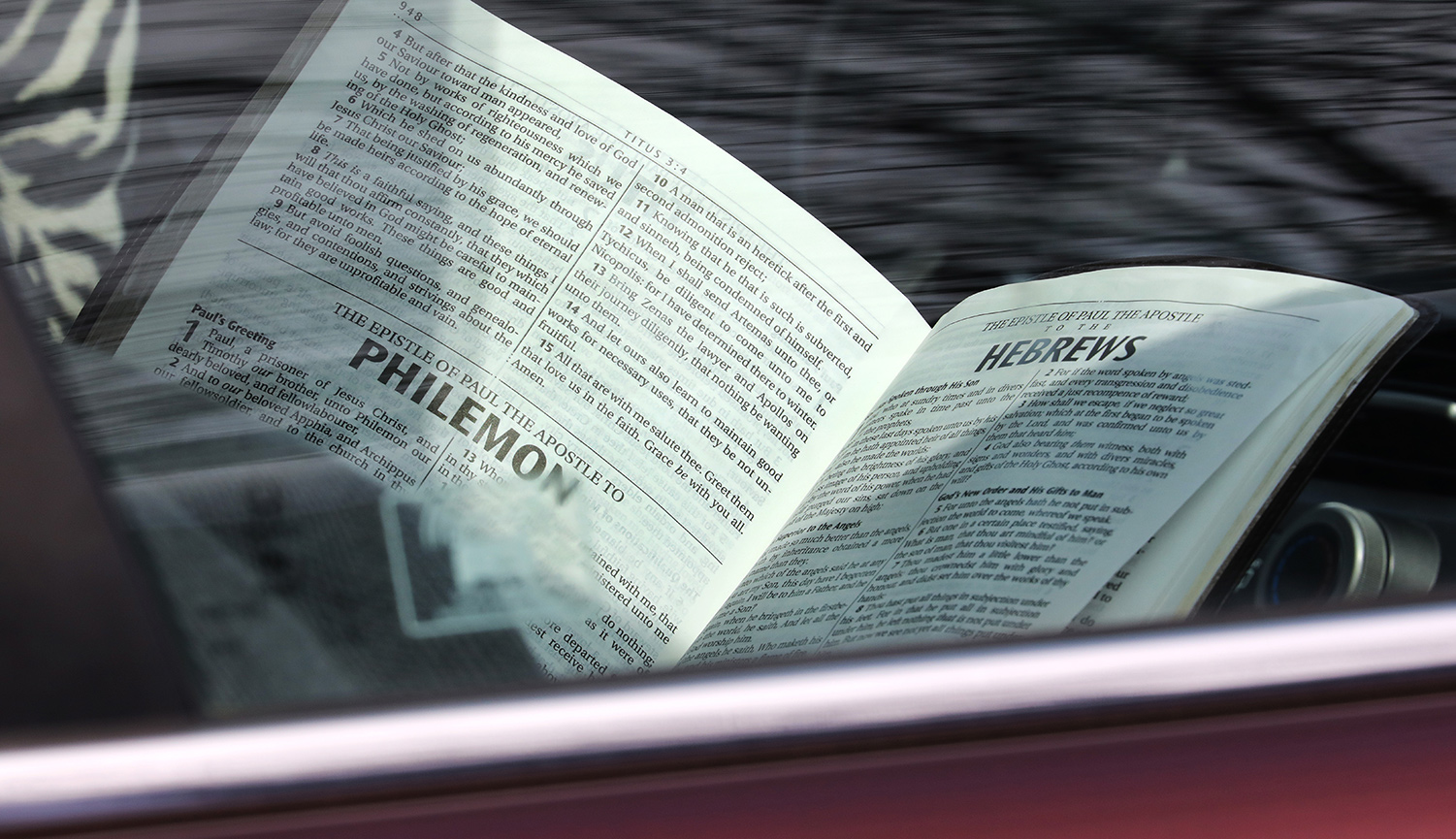

The principal obstacle to a theologically serious rapprochement of Jews and Christians lies, as is well known, in supersessionism, which McClay defines as the Christian notion that “the promises that God had made to the Jews were withdrawn because the Jews had failed to keep their side of the bargain.” As a result, the older arrangement “was replaced by a new covenant, a second covenant that, superseding the Abrahamic one, was built around the person of Christ and his body, which was the Church, the New Israel.” In McClay’s view, this replacement is, however, self-limiting, for “the Christian story, despite diverging decisively from the Jewish one, can never be intelligible apart from it.” The organization of the two-testament Bible of the church is itself proof: the New Testament “requires Christians to recognize the authoritative claims of the Hebrew Bible, the so-called Old Testament.” By the very fact that the New Testament understands itself in relation to the Old, it can never fully supersede it.

What is more, as McClay sees the matter, supersessionist theology is not actually a New Testament teaching but rather a post-scriptural innovation that “in fact barely existed in the first century after Jesus.” Citing the Anglican theologian Gerald McDermott, McClay observes that “while the Church itself is never called the New Israel in the New Testament, the name ‘Israel’ appears 80 times there, and always to refer to the Jewish people or the Jewish polity in the land—or to the land itself.” In light of the founding of the state of Israel in 1948 and the return of Jews to sovereign power in the Land of Israel, “that fact,” he adds, “should take on added meaning today.”

In the 2nd century CE, as McClay sees the matter, an ominous change takes place. The importance of the Jews as a real, flesh-and-blood people and their distinctive, identity-conferring practices, such as kashrut (dietary laws) and brit milah (ritual circumcision), decline precipitously among Christians, and “the people of Israel . . . become reinterpreted as a precursor, a prefiguration of the universal Church.” The new Christian symbolism renders the existence of actual Jews as a distinct, extant community as at best pointless and at worst an offense to the highest truth, the truth of the Gospel. The persecutions, often murderous, to which the supersessionist doctrine gave birth, set the stage for the quest for a reconciliation that has, in fits and starts, been going on in the West throughout modern times and, for obvious reasons, most intensively since the Holocaust.

McClay does not imagine that supersessionism can be eliminated altogether. Rather, citing the Jewish theologian David Novak, who thinks some degree of supersessionism is indispensable to both Christianity and Judaism, his key question for Christians is “how to make that remaining vestige sufficiently ‘soft’ (Novak’s term) to be true to itself while also recognizing the uninterrupted distinctiveness of the Jews and the perseverance of their unique covenant with God.”

This is a difficult question. To answer it, McClay follows McDermott (and many others over the years) in turning to Paul’s Letter to the Romans, where the apostle to the Gentiles “says that Jews who have not accepted Jesus are still ‘beloved’ of God ‘for the sake of their forefathers’” and that the promises to them are irrevocable. With that as the foundation for their theology, Christians should be able to affirm the continuing importance of the Jewish people and their right to the Land of Israel—surely an epoch-making shift worthy of much more attention than it has heretofore received.

II.

Is it true that supersessionist theology is a product of 2nd-century Christianity and barely found in the New Testament itself?

It is certainly the case that the diverse documents of the New Testament are enormously difficult to interpret and that some highly regarded scholars now pursue approaches that soften or sometimes even eliminate the ostensible anti-Judaism found in various passages within it. It is also true that renewed scholarly attention to Second Temple Judaism, energized in large part by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, has revolutionized the relationship between what we (using terminology that is less than ideal) call “Judaism” and “Christianity” at the time that the latter first appeared.

Unfortunately, none of this validates the claim that the offending theology is a product of post-scriptural Christian thought.

Let us take as our first example the interpretation of the Jewish people as “a precursor, a prefiguration of the universal Church.” In one of his earliest letters, Paul interprets the stories in Genesis of the slave woman Hagar and her son Ishmael, on the one hand, and of her mistress Sarah and the latter’s son Isaac, on the other, as an allegory for the relationship between two covenants. The first, associated with Sinai, represents slavery; the second, associated with “the Jerusalem above,” represents freedom. “Now you, my friends,” writes Paul to his Gentile correspondents, “are children of the promise, like Isaac. . . . So then, friends, we are children, not of the slave but of the free woman.” Significantly, he follows this allegory with a characteristically bold statement of his overall theology: “For freedom Christ has set us free. Stand firm, therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.” (Galatians 4:21-5:1. Unless otherwise noted, my New Testament quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version.)

This text nicely illustrates the truth of McClay’s point that “the Christian story, despite diverging decisively from the Jewish one, can never be intelligible apart from it.” Without having read the Abrahamic narratives of Genesis, one would simply have no idea what Paul is talking about, and his argument would hardly persuade anyone who did not assume that those narratives are in some way endowed with authority. But the message itself sounds not only alien to Jewish ears but in contradiction to explicit rabbinic teaching, some of which was probably formulated as a refutation of the Christian thinking expressed here. Sinai as slavery? A famous midrash in the name of a rabbi of the early 3rd century CE asserts quite the opposite: “For there is no free man except for one who occupies himself with the study of Torah” (Avot 6:2).

And what about Paul’s claim that his Gentile correspondents are, like Isaac, the children of Sarah? To be sure, this particular text does not deny that status to non-Christian Jews and might conceivably, as some scholars have claimed, support something like a dual-covenant theology in which the negative view of Torah applies only to Gentiles in the Church and not to Jews. In my judgment, the most natural reading of Paul’s allegory is nonetheless one that properly reckons with Paul’s emphatic insistence that one of the two covenants represents slavery and the flesh, and the other, freedom and what Paul calls “the promise.” Only one of the two covenants (the latter) is appropriate to Paul’s audience. If he had no negative associations with the longstanding covenant with the Jews, his slavery metaphor did a fine job of hiding his true convictions.

By Paul’s time, Judaism, or at least some versions of it, also had a way to make Gentiles “like Isaac.” Conversion, in the case of men, required circumcision. In early Christianity, or at least in Paul’s version of it, circumcision was already viewed as a highly negative practice. The low estimation is hardly an innovation of 2nd-century Christian writers: “For in Christ Jesus,” the apostle writes, “neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything; the only thing that counts is faith working through love.” A few verses later, he goes so far as to express the wish that those who preach circumcision would castrate themselves (Galatians 5:6,12). If he thinks there is something equivalent to “Christ Jesus” for non-Christian Jews, something that makes ritual circumcision (he is not talking about hygiene) precious, Paul again disguises his view well.

What about McDermott’s and McClay’s claim that in the New Testament “Israel” always refers “to the Jewish people or the Jewish polity in the land—or to the land itself.” Here, again, the matter is more complicated than an unqualified, anti-supersessionist interpretation suggests. Consider this instance, from what may have been Paul’s last letter:

It is not as though the word of God had failed. For not all Israelites truly belong to Israel, and not all of Abraham’s children are his true descendants; but “It is through Isaac that descendants shall be named for you” [Genesis 21:12]. This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as descendants. (Romans 9:6-8)

Although, as often with Paul, ambiguity and uncertainty abound here, it would seem that Paul’s Israel excludes some Israelites. Just as in Genesis, only Isaac and his descendants and not all of Abraham’s progeny inherit the covenant God makes with Israel’s first patriarch, so here only “the children of the promise” and not “the children of the flesh” are genuinely members of Israel. Although Paul does not literally call the Church “Israel,” he comes exceedingly close to it here. Similarly, consider his expression “Israel according to the flesh” (1Corinthians 10:18, departing from the New Revised Standard Version, which is insufficiently literal here). Does it not imply the existence of another Israel, one that, to invoke a familiar Pauline dichotomy, is “spiritual” instead?

The same general point about the Church as Israel must be said of other texts as well, especially this one from a letter ascribed to the apostle Peter:

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light.

Once you were not a people,

but now you are God’s people;

once you had not received mercy,

but now you have received mercy. (1Peter 2:9-10)

These verses, heavily dependent on the Hebrew Bible (especially Exodus 19:5-6 and Hosea 2:25), apply the affirmations of chosenness in the Jewish source to the writer’s Christian correspondents. Although this passage, too, does not happen to apply the name “Israel” to the Church, it leaves no reasonable room for the proposition that there is some other group with a claim to be “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people.”

Some New Testament texts go further and explicitly parry the claim that the special status of the Jews has a continuing theological rationale. Whereas McClay calls for the Abrahamic covenant to have “an enduring place” in Christian theology, two of the three synoptic gospels present John the Baptist as disparaging Abrahamic descent. “Do not presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our ancestor,’” he chastises both the Pharisees and the Sadducees in Matthew’s version, “for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham” (Matthew 3:9). Good works alone avail against the divine wrath whose advent John announces; Abrahamic ancestry does not.

In the gospel of John, it is Jesus himself, angrily disputing with “the Jews,” who counters their claim that “Abraham is our father.” He does so by applying to them a paternity that he thinks better accords with their actions: “You are from your father the devil, and you choose to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning and does not stand in the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies” (John 8:39, 44). In this instance, it is the Jews’ disbelief in Jesus that utterly disqualifies their Abrahamic descent. Here, there is a strong analogy with the stream in Paul’s thinking that asserts that “those who believe are the descendants of Abraham” (Galatians 3:7). It is faith, not descent (or good works), that puts one into the family of Abraham.

Admittedly, this stream contradicts the same apostle’s affirmation in a later letter that the Jews remain “beloved, for the sake of their ancestors” (Romans 11:28), mentioned by McClay and McDermott; I make no claim that Paul was consistent over the years or lacking in ambivalence. But even here, where Paul (to put it too simply) is pro-Jewish, there is no reason to think he is pro-Judaism, that is, sympathetic to practitioners of the religion of Torah and commandments who are unmoved by Jesus’ special claims for himself. And it is far from clear that his pro-Jewish sentiments included an expectation that Jews would ever reassume sovereignty in the Land of Israel.

In sum, the supersessionist dimension of Christian theology, though it becomes more intense and less nuanced in the 2nd century, begins earlier and is amply attested in the New Testament itself.

III.

Given how deeply rooted in Christian scriptures the supersessionist theology turns out to be, it may seem that McClay’s celebration of Christian Zionism is misguided. But a closer look at the options facing the sympathetic Christian suggests, in fact, that his confidence is not in the last analysis misplaced.

In my experience, some Christians say that their faith is in Jesus, not in their Bible or what the Bible says about him. Recovering the historical figure of Jesus from the early Christian sources about him is, of course, a hugely complex enterprise, one that is necessarily full of conjectures and resistant to consensus. Nonetheless, in the minds of many historical-critical scholars of the New Testament, the historical Jesus was thoroughly rooted in the Judaism of his time—itself a famously heterogeneous phenomenon—and did not seek to replace the Jews with another group or to set aside the Torah.

If those scholars are right, then in some ways the New Testament is more like the intensely supersessionist Christian literature of the 2nd century and later than like the actual teaching of Jesus. This, in turn, allows Christian believers to acknowledge the historical contingency of the biblical witnesses—in particular, the fierce disputes with some Jewish groups in which they took shape—without abandoning their devotion to Jesus.

Few indeed, however, are the Christians who base their faith in Jesus on this or that historical-critical reconstruction. More common, especially among certain Protestant groups in American and the developing world, are those who claim to have had a personal revelation in one form or other. The Jesus these believers confess may conform to the New Testament figure—there, too, the portrait is far from unitary—or he may not. He may, instead, teach something much more sympathetic to the Jews and Judaism and the Jewish claim to the Land of Israel.

A closer examination of supersessionism itself, its nuances and tensions, also suggests a way forward for Christian Zionists.

What is commonly but somewhat ham-handedly called “supersessionism” has its origins in notions of prophecy and fulfillment, or foreshadowing and realization. The new necessarily moves beyond the old but, as McClay points out regarding the two Testaments of the Christian Bible, remains incomprehensible without it. That tension between the novelty of the new and its inescapable dependence upon the old is quite widespread; it certainly has its analogies in the Hebrew Bible and Judaism. I think, for example, of an oracle in the book of Isaiah that exhorts its hearers, “Do not recall the events of old/ Or think about the things of ancient times!/ For I am about to do something new” (Isaiah 43:18-19)—which turns out to look an awful lot like the events in the wilderness in Exodus and Numbers.

For Christians, the relationship between the testaments is key to the issue of supersessionism. Here, there is a range of possibilities. On one extreme is the position well represented by a famous poem about Passover by Melito of Sardis, a 2nd-century bishop. There the people Israel and their Torah are described with words like “sketch,” “type,” and “analogy,” whereas the Gospel and the Church are characterized with terms like “truly real,” “true value,” “fulfillment,” and “repository of reality.” Melito’s point is that after the advent of Jesus and the founding of the Church, the people of Israel and the Torah have become “useless” and “worthless.” In words that in light of the Holocaust sound chilling, he goes so far as to say that when the reality comes into existence, “the type is destroyed.”

Of a similar bent but less extreme is the affirmation a conservative group called Evangelicals and Catholics Together made in 2002. For them, the New Testament is “the authoritative interpretation” of the Old. About this, John Goldingay, an Old Testament scholar at Fuller Theological Seminary, offered a telling response. “It is inappropriate to describe the New Testament as the ‘authoritative interpretation’ of the Old without adding that the Old Testament is the authoritative interpretation of the New,” Goldingay observed, “especially as the New shows more signs of recognizing the authority of the Old than of reckoning it has authority over it.” He goes on to say that “a main significance of the Old Testament is to show us that God has a broader agenda than we think when we focus exclusively on Jesus.”

In the context at hand, I take this to mean that however much New Testament sources may present the Gospel and the Church (not, by the way, universal humanity) as superseding the Torah and the Jewish people, respectively, the New Testament does not supersede the Old. In the Christian thinking exemplified by Goldingay, the Old Testament retains a voice of its own in Christian theology, even if it cannot ignore the voice of the New Testament—and, for some major Christian groups, the authority of post-scriptural doctrine that has grown over the centuries as well.

Another way to come to the same point is to recognize the historical fact that the interpretation of the Old Testament in the New rarely corresponds to the plain or contextual sense. Instead, it very often falls in the domain of what Jewish tradition calls “midrash,” a creative, theologically driven, non-contextual mode of interpreting biblical verses. To some substantial degree, then, the New Testament is to the Old Testament as midrash is to the immediate contextual sense (in rabbinic terminology, the p’shaṭ). Just as in Jewish tradition there is a longstanding tension between midrashic and plain-sense exegesis, with neither able to supplant the other, so there is in Christian tradition an analogous tension between the two testaments (not to mention the same tension in the interpretation of any piece of scripture).

Within that tension, there should be plenty of room for Christian Zionism.

IV.

Even if one agrees that there is a warrant in Christian theology for Zionism, a key question remains open: what is the proper limit of Christian support for the state of Israel? McClay notes that some Christian Zionists “understand the restoration of Israel as a fulfillment of biblical prophecy and a token of the end times.” To them, as to some Jews as well, the answer, I would think, is simple: there is no limit, for the state of Israel operates under the providential guidance of the God who made an indefeasible grant of the land to the Jewish people. To fault the state or to support its withdrawal from any land within its biblical borders is to act against God and His ultimate triumph.

On the other side, one can cite statements by various churches of what is still sometimes called—though now anachronistically, in light of their dwindling numbers—“mainline Protestantism.” Here is an excerpt of one issued by the Presbyterian Church USA in 1987:

The Genesis record indicates that “the land of your sojournings” was promised to Abraham and his and Sarah’s descendants. This promise, however, included the demand that “You shall keep my covenant. . . ” (Genesis 17:7-8). The implication is that the blessings of the promise were dependent upon fulfillment of covenant relationships. Disobedience could bring the loss of land, even while God’s promise was not revoked. God’s promises are always kept, but in God’s own way and time.

Here, it is not only premillennial dispensationalism that is rejected; it is also the belief that Israel should be evaluated by the same standards as any other country. But notice how these Presbyterians, however much they may dislike Christian Zionism, themselves view the state of Israel through a biblical lens. The difference is that the Presbyterians stress the conditional dimension of the land promise, which is also well attested in the Hebrew Bible (though the Genesis text they cite is not a good example), rather than the unconditional dimension prominent among those, whether Christian or Jewish, who believe the restoration of Jewish sovereignty signals the onset of the end time and is therefore irreversible.

To most Jewish supporters of Israel, the double standard evident in church statements like the one quoted above is galling. And, to be sure, it would be wrong to attribute the offending element only to the influence of biblical theology. In my judgment, it also has sources in traditional theological anti-Semitism, suppressed for a generation by the Holocaust, and in the increasing power of leftist ideologies over the “mainline” churches, which in some instances overrides any biblical or other traditional constraints.

Still and all, one cannot discount the biblical element in the thinking of either the Christian supporters or the Christian critics of Israel. It is wrong to assume that all those who view Israel through a biblical lens will be supporters of Israeli policies. What I have tried to argue is that although the Christian supporters face obstacles that are powerful and date from as early as the New Testament documents themselves, they now also have formidable resources with which to make their case.

In any event, for reasons that Wilfred McClay has so nicely laid out, for theologically serious Christians the Jews are just not the same as any other people. And they never will be.

More about: History & Ideas, Jewish-Christian relations, Supersessionism