Class facilitators Laura Tuach (left) and Melissa Wood Bartholomew discuss during the executive education course.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Executive education with a soul

Divinity School course learns from history how to become a force for good

It wasn’t what LaQuisha Anthony was hoping for, but it turned out to be what she needed.

Five years ago Anthony founded V.O.I.C.E. (Victory Over Inconceivable Cowardly Experiences), a support network for sexual abuse survivors in her native Philadelphia. The nonprofit focuses on helping women of color and removing the stigma around sexual violence.

Earlier this year, she signed up for “Making Change,” a summer executive course at Harvard Divinity School (HDS), expecting to pick up some new skills and tools to become a more effective leader. She found much more than that. Anthony left with a good dose of inspiration and the new goal of becoming a broader force for good in the world.

“It was like a pilgrimage for me,” said Anthony. “It touched me deeply. It reaffirmed the idea that change is possible, and gave me a new approach, which is that I need to engage all people, all cultures, and all religions in order for us to see a collective change in our society and our world.”

Anthony was one of 19 participants in the intensive, four-day class designed to offer a different type of value from those offering management skills or best business practices.

Divinity School faculty ran the program like a personal-development retreat mixed with a graduate seminar on ethical issues such as racism, inequality, migration, conflict, and peace.

Besides attending lectures, students took part in small-group conversations, where they engaged in self-reflection exercises on how to become agents of change. Because the School teaches theology and religious studies, there was the option to partake in religious practices, such as Buddhist meditation, Jewish Torah study, and contemplative Christian prayer.

“Often people come to these courses thinking that they’re going to be making a five-year plan with bullet points and know what to do when they go home,” said Stephanie Paulsell, Susan Shallcross Swartz Professor of the Practice of Christian Studies and faculty chair for executive education. “We’re trying to offer a richer, deeper experience that involves thinking about the relationship between personal transformation and transformation in the world around us.”

Now in its second year, the course attracted ministers, businesspeople, lawyers, artists, and nonprofit founders and administrators.

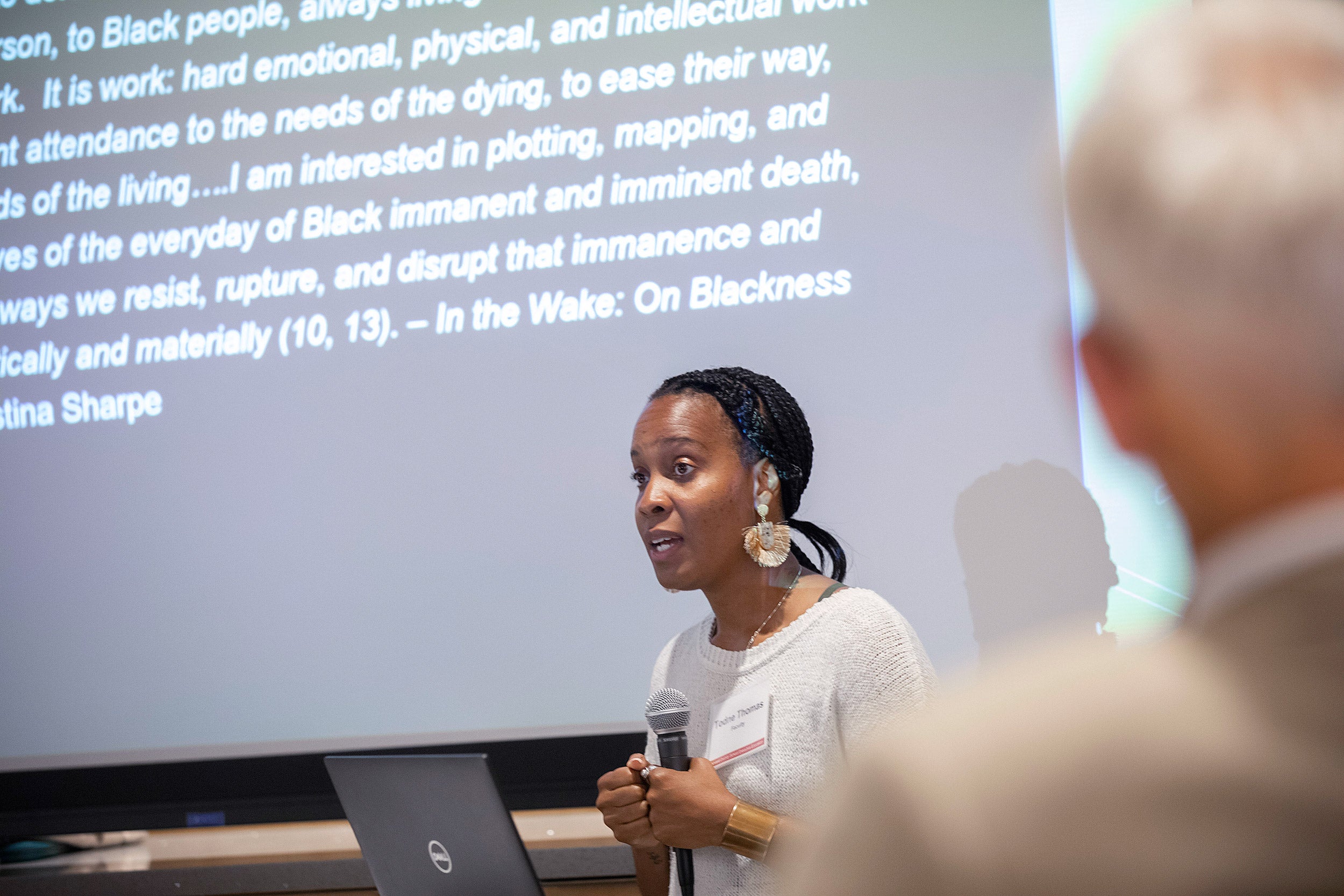

Assistant Professor of African American Religions Todne Thomas gives a presentation to executive education students.

“We’re here because we’re all seeking change,” said Vincenzo Pascale, a journalist and a representative of Migrantes, an NGO affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church at the United Nations. “The program validated my work and the exercises helped me bring forward some ideas I’ve been contemplating on how to increase our organization’s leverage.”

For Elizabeth Rovere, M.T.S. ’95, a New York City-based clinical psychologist who took part in last year’s pilot, the course helped build a sense of community among the participants, who came together to learn from each other despite their differences.

“It was a meaning-making ‘inspiration tank,’” said Rovere by email. “It was like going back to school for an executive immersion to have your eyes wide open in a different way. It was deeply thoughtful and spiritual, anchored in history, theology, and ancient wisdom.”

The course put an emphasis on history. Students learned about the history of Mexico and of race there and in the Caribbean; the role of religion in national and regional conflicts; the saga of peace-building efforts in Ireland; and the evolution of the Civil Rights and migrant farmworker movements. For many participants, the focus on U.S. history, especially around race and borders, was revelatory. It led to conversations that are necessary for healing, Paulsell said.

“People are hungry for these kinds of conversations,” she said. “The program gives people a chance to have these conversations that everybody wants to have but are scared to have. We all learned that we need to become familiar with our history and confront that history together if we’re going to make any kind of change.”

A session about white supremacist Dylann Roof’s murder of nine African-American churchgoers in Charleston, S.C., in 2015 made an impact on the audience. Assistant Professor of African American Religions Todne Thomas spoke about the history of the black church and its role as a center of black social life.

“What was Dylann Roof trying to kill?” Thomas asked. “We know that Dylann Roof killed five praying black congregants, right? But the question is bigger than that. What was Dylann Roof trying to kill? … Why has the black church been a sustained target of violence in the United States?”

Anthony was so touched by Thomas’ lecture that she wrote a poem encapsulating the lessons she learned during the course, from sharing her hardships as an African American woman to helping people become more aware of their privilege to realizing the power of working together. “I see us at home,” she wrote, “home in a sacred place.”

“We have to come out of our own silos,” said Anthony. “If we want to create change in our country, we have to understand our shared history and be able to accept where we fall in the narrative, even if it’s uncomfortable.”