This Religions and the Practice of Peace Colloquium explores the intersection of racism, oppression, urban trauma, disaster, and other social realities faced by those desperately in need of peace. More than the absence of violence and war, we need the aggressive and proactive generation of peace, healing, and bliss under a continuing barrage of compromises to health and well-being. What is peace? How do we create it when there is little? Who deserves peacemaking?

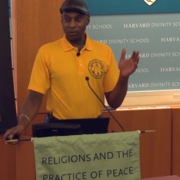

Speaker: Zumbi, founder, Kilombo Novo; director, Trauma Response and Recovery at Boston Public Health Commission

Moderator: Emily Click, assistant dean for ministry studies and field education and Lecturer on Ministry at Harvard Divinity School

Discussant: David Harris, managing director, Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

DAVID HEMPTON: So welcome, friends and colleagues, to the Religions and Practice of Peace Colloquium. Happy Valentine's Day. I'm David Hempton, Dean of the Harvard Divinity School. And we want to thank you all for spending this very special evening with us, which is very much apropos, the topic of love.

So on behalf of RPP and the Divinity School, I'd like to extend a very warm welcome indeed to our featured speaker, Mr. Courtney Grey, who's right over here. Also known as Zumbi. Zumbi, thanks for being here.

COURTNEY GREY: My pleasure.

DAVID HEMPTON: And to tonight's discussant, Dr. David Harris, who's sitting right here, thank you, David, for helping us out again and for the co-sponsorship by your program, the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at the Harvard Law School. Also, thanks to our moderator this evening, professor Emily Click, my good friend and colleague. Thank you, Emily, for devoting an evening to us.

And we'd like to express our appreciation to all the RPP's generous donors, supporters, helpers, including Karen Budney and Al Budney, for helping to make these and other RPP activities possible. We're really grateful for support. I'd also like to thank Liz and Demi and our student assistants and staff and facilities, everyone who has contributed time and expertise to this evening. Thank you so much for all your work. Yeah. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

And a very special thanks to Kayla Smith over here, who connected us with Mr. Grey and has contributed a great deal to the preparations for this evening. So thank you so much for all that you've done.

[APPLAUSE]

So at these RPP Colloquium sessions, we'd like not only to learn about peace but also to practice peace with one another. So to begin two of our graduate assistants, Kayla and Nicole, will offer introductory words from the RPP team for our time together. So I'm going to invite Kayla and Nicole to come and get us started. Thank you so much.

[APPLAUSE]

SPEAKER 1: We are gathered to advance sustainable peace and to learn and grow in our peace practice. Let's begin by cultivating engaged, caring, and appreciative relationships here and in all of our settings. Sustainable peace is a complex endeavor to which everyone has much to contribute. We would like to share some of our aspirations, which we hope you'll help us keep in view.

As members of one human family, how can we relate to one another in a spirit of love and friendship despite our differences, disagreements, and limitations? How can we acknowledge contributions from all cultures and traditions as equally valuable and appreciate and benefit from everyone's experiences and wisdom?

How can we attend to our biases and to oppressive systems of power based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, and other factors and empower one another to promote justice and shared flourishing? How can we work for equity and justice in ways that are humanizing, build connection, and promote healing and transformation? What wisdom, knowledge, and spiritual resources do we need to do this?

Please join us in creating a courageous, respectful, and forgiving space conducive to deep sharing, deep listening, and mutual learning. Let's practice sharing questions and comments as well as concerns and differences of view while maintaining a validating environment across difference. We are interdependent, and we need one another to expand our vision and help us consider our blind spots. So let's seek deeper understanding when we see things differently, draw upon our spiritual resources, and support one another in constantly improving our approach to each other and to what we do.

SPEAKER 2: We acknowledge that conversation of this kind is challenging. Listening to other perspectives and sharing our own makes us vulnerable and can be uncomfortable. It can be hard to process in the moment and to find words. At the same time, few things are more essential to our growth and collaboration towards sustainable peace, so we thank you all in advance.

To give you an overview of tonight's session, we'll begin and end with a moment of silence. After the introductions and Mr. Grey's presentation, we'll have a brief response from Dr. Harris. Then, Mr. Grey, Dr. Harris, and Professor Click will engage in some conversation. After that, we'll give you all five minutes to discuss your thoughts with your neighbors. Finally, we'll invite your comments and questions.

If there are ideas or concerns that you're not able to raise during the session, please include them in the survey that we've given you in your dinner box, which we'll give you time to complete later during the session. Additionally, you're also always welcome to speak to us at the reception or to email us at the address on the RPP website.

We've also passed around small sheets of paper. If you have questions that come up during the session, we'll be collecting those right before the question section starts. So please look out for baskets to collect those questions. We might not get to all of them, but please know that we appreciate your thoughtfulness.

Let's begin now with a moment of silence, contemplation, or prayer in gratitude and remembrance of all lives who are suffering here and around the world and to set our intentions for our practice of peace.

Thank you all.

DAVID HEMPTON: Thanks, Kayla and Nicole. Thank you everyone for participating in that.

In the emerging One Harvard Sustainable Peace Initiative, we're exploring with faculty, students, and friends here and around the world ways to foster a trend to mainstream sustainable peace as a goal of leadership across sectors and communities. As a social historian and as someone who lived through the troubles in Northern Ireland, I know that we all bring many different conceptions of peace and approaches to peace informed by our particular experiences, and perspectives, and traditions, and histories.

Our thinking and approaches in the academy and institutions need to become much more informed by expertise in our communities and spiritual and cultural traditions. This demands that we come together locally as well as globally to explore our varied understandings of what peace is and what the various practices we bring to it. The most basic question that we ask everyone in the Sustainable Peace Initiative is, what is your vision of peace, and how can we make it substantive, shared, and sustainable and realistic?

We're honored and grateful for the opportunity to hear tonight from an influential leader in Boston with great breadth and depth of experience and expertise in this very question. Mr. Grey will share wisdom on the topic for tonight, which is Indigenous Perspectives on Peacemaking in the face of Racism, Religious Exodus, Oppression, and Unfair Exposure to Trauma and Disaster.

First, I'd like to briefly introduce our moderator. Professor Emily Click has served for 13 years as Assistant Dean for Ministry Studies and Director of Field Education and Lecture on Ministry here at the Divinity School. She is an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ. Prior to completing her PhD in religious education and leadership at Claremont School of Theology, she served two UCC congregations in pastoral roles in California.

She teaches courses at HDS in the areas of education and leadership. She works with all of her students in field education, who are placed in sites that are widely diverse. That's one of the very most important things we do at the Divinity School with and for our students. The multi-faith MDiv at HDS means that these placements engage students in real communities-- religious communities, nonprofits, political campaigns, art institutions, and many other types of situations at home and sometimes overseas.

She is deeply appreciative of the imaginative engagement present students have with societal injustices. She has long held interests in how best to prepare students for real actual leadership challenges that they will face, including the complexities of racial injustices, conflict mediation, shifting perceptions and understandings of what it means to be religious. So it's a very great pleasure for me to introduce my very wonderful colleague Emily Click who will introduce our two speakers and moderate our session. Emily, thanks so much for being here.

[APPLAUSE]

EMILY CLICK: Thank you, David. And I want to extend the warmest of welcomes to all of our guests tonight, most especially Zumbi. We're so glad and I'm really excited-- you can just feel the excitement with folks in bright yellow shirts. And we can't wait to hear from you and also our esteemed friend Dr. Harris, who is working in partnership with our program tonight. So thank you all.

As I was thinking about tonight, I was thinking about the course that I'm teaching this semester. It's a course that specifically focuses on leadership and administration. Most of our courses here have something to do with leadership. But we look at what does it mean to become leaders that are informed, at least by religious studies, and often by the deepest of religious values?

And we begin the course by saying that leadership begins with listening. Now, that's not the usual definition we see in the public forum today. Much of what stands for leadership is standing up and telling people what to do.

That works of course, when you have very simple problems and everybody knows exactly what the problem is and you can find the solution. And then you get to have a leader who says what the problem is and tells people what to do. We're not really interested in those kinds of problems.

We're interested in the complex situations that often mean we don't quite understand what the problem is. And maybe nobody does. And just defining the problem is itself a problem. And then maybe there is a solution, maybe there isn't a solution. And then what do we do? So how do you stand in those situations and build communities who can make some traction, in the midst of the kind of problems that matter and count?

So we say leadership begins with listening and the semester begins with listening because we want to convey that the leadership we're talking about in this community is leadership that has, as its foundational discipline, listening-- listening deeply. What I'm talking about is not this passive stance of "I don't know, you tell me." It's an engaged stance that is also humble, and that engages in a way that pays attention to what we do not know.

So very often in academic culture and in the culture I come from, we listen in a way that just can't wait to tell. You know, I'm composing in my mind what I'm going to say once you've finish whatever it is you're saying. No, that's not listening. Listening is paying attention to the new things you're hearing that you didn't know. So that what happens then is an inquiry that expands what the person you're listen to is saying.

So I want to invite you into exactly that kind of space tonight. We have an amazing opportunity to listen and to hear some things we don't know enough about. I'm sure that's varied amongst us. Some of you know a great deal, and others of us less. But if each of us can pay attention to what we do not know, we can then listen with a humble ear, which will inform us as we go forward.

So I was quite fascinated when I went and read a 2005 article that Courtney Grey co-authored with John Harris, in which he reported on the very scholarly ethnographic research he had done. And that research did what? It went and listened in a way that we too rarely do in the midst of a very complex problem, which is why young black men suffer traumatic injury.

What do they have to say about it? What do they understand about their experience? What do they understand about what kinds of responses they must make to the injustice that they experience in this ongoing violence and injury? That may not be a fair summary. I invite you to correct that if that's not.

But I was just really thrilled that you model such listening that I'm trying to invite students into. So I cannot wait to hear more from you. And so I'm going to simply introduce our presenter and our discussant so that we can get going.

And so Mr. Courtney Grey, also known as Zumbi, is the founder of Colombo Novo, a group of youth community members, clinicians, and agency professionals that help people of color heal from traumatic events and reduce community violence. As a trainer of trainers for some--

COURTNEY GREY: Partnership.

EMILY CLICK: Thank you. --partnership with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, he has built a highly skilled international network of over 500 partners, able to deploy these techniques in community settings and for multiple ethnocultural groups. As director of Trauma Response and Recovery at Boston Public Health Commission, he has served over 800 youth and adults annually in the immediate aftermath of homicide, suicides, accidents, and natural or human-caused disasters-- such as the Boston Marathon bombing, and most recently, the Parkland, Florida school shooting.

He's initiated in multiple indigenous cultures and has taught internationally and has served Lakota, Sioux, Cambodian, Bosnian, Cape Verdean, Haitian, and several other populations after trauma and disaster. He has taught internationally and has spoken at the White House to Congress, the Department of Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services.

He bases his work on the integration of evidence-informed disaster behavioral health practices and indigenous traditional approaches to human development, restorative justice, and healing. As one of the city's racial justice and health equity trainers, Mr. Grey helps BPHCs 1,100 employees address the negative impact social determinants have on the most vulnerable populations. Mr. Grey has conducted qualitative research in the National Institute of Mental Health K08 Study on penetrating injury and co-authored pathways to recurrent trauma among young black men, traumatic stress, substance use, and code of the street.

Dr. David Harris, who will be our discussant tonight, is the Managing Director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice, and a lecturer at Harvard Law School. Prior to his position at the Houston Institute, he served as Founding Executive Director of the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston.

Dr. Harris is recognized as a leading voice for civil rights in the Boston region, and has spoken extensively at local, regional, and national forums on civil rights, regional equity, and fair housing. He previously served with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and with the US Commission on Civil Rights.

He holds a PhD in sociology from Harvard University and a BA from Georgetown University. Dr. Harris currently chairs the Massachusetts Advisory Committee to the US Commission on Civil Rights. I think we're ready to hear everything you want to share with us. Welcome.

[APPLAUSE]

[TRIBAL MUSIC]

[NON-ENGLISH VOCALIZING]

COURTNEY GREY: I think I heard in the-- well, first of all, I can't stand when people read my bio. You write a bio to impress people because people who look like me don't get to certain places. So you write a bio that's pretty deep. You're showing all your stuff there. But I think when I do these types of talks, they need to say I'm Maurice and Lena's son. That's all you need to say. That's the most important thing I can say up here.

I want to bring a few people into the room today. The first is going to be a man named Prem Das. Prem Das is a very thin White man, my height, lots of gray hair. I probably would call him a hippie in another life. And he is initiated in the Lakota practice. So I'm bringing up Native people here today because I'm sure this building is built on top of the land that was inhabited by Natives before colonization and oppression started.

Actually bad things could have happened here. We get the luxury of being here today. Maybe I'm going to impress you in 45 minutes. What can you do in 45 minutes anyway? And I think actually all of us together here being together for 45 minutes or so is equal to on person working for seven days straight. That's the human impact of us being in this room.

So hopefully at the end, and I think it's more about the end than what we say here today, people get motivated to work in some kind of way that we can affect huge changes in peace. So back to Prem Das. Prem Das got me involved with this thing called the International Day of Peace and Ceasefire from the United Nations, a very powerful thing. Two million people doing a minute of silence at the same time, at 12 noon, on 9/21-- which is deliberately 10 days after 9/11-- 250 countries, all kinds of things going on.

And while there, I'm the only guy like me in the room. Most of the planning meetings, meeting somebody who's from Jamaica then grew up in a very bad neighborhood and representing another experience than most of the people that were in that room. And I'm saying, wait. When you guys do this minute of silence, is it the folk singers and the white dove thing? Or is it about these people that experience severe compromises to their notions of peace on a daily basis? Is this making sense what I'm saying?

If we're looking for people who don't have peace, it's not too hard to find. I think in 10 minutes we could be me somewhere right now driving, and we'd be in a neighborhood that has experienced incredible things. We have young people in the back of the room, they fight everyday and advocate for things. And I don't know if when I'm in academic settings if the notions of peace are the same as what those young people experience every day.

So the good thing about having a presentation is that it can structure the talk. Because there's a lot to do, and I'm going to try to say it in a short timeframe. And frankly, I think I made a pretty cool presentation. Except my clicker thing is gone. Let's see if this works. Nice.

OK, so basically I'm already saying today that there's a disparity in peacemaking. Those of us who might know peace, somehow it's not getting to the people who need it. And my jobs have-- I guess some of the things that were in my bio are specifically going to places like you just had the marathon bombing. Somebody just shattered your peace. Go to Parkland, Florida. They just shattered your peace-- 17 people.

Yet I do that in the context of a world where 9 people from a black AME church in South Carolina-- that's pretty bad. And nobody with the skill sets that I have and my colleagues out was sent there. I mean, they did a good job. But there's a disparity in how we even-- what I'm calling deployable peace, peace that you send someplace.

So who needs it the most, and what are we doing for them in the absence of peace, is a question I'm exploring. And also how do we frame peace? And so yeah, that's my name. That's an organization that I represent. And here's me pondering these notions. It's not actually me. But I thought it was a cool picture of a guy that's pondering, "where we make peace?"

So literally how are we going to address-- by the way, you're starting to see the animation here right? How do we address these disparities? And first is do we even know what the experience is for those that are most affected by it? I'm going to do a screen-change here. Let's see if it works elegantly.

So those that are most affected, where are they and how well do we even know their experience? I'm going to try to bring some people in the room. I think there was a little bit of permission granted. Thank you. Because I wasn't going to talk a lot about that particular study. But it was a pretty tough study to do because we were interviewing people who had been shot, or stabbed with penetrating injury, that were transported to Boston Medical Center.

130 men over three years were interviewed, I think as they got to the hospital. And three months later, a good colleague of mine, Irvine, was shepherding us through this. Her job also is one of showing up for people who have-- I'm just going to call it peace compromised.

We show up for these people on a daily basis. And there I got my first really good dose, from an academic standpoint, of what it's like to not have peace in your life and the challenge of making that peace. We're bringing that peace back.

And then if that's the case, how well are we doing with peace? And is there a desperate need to increase the outcomes of this equal system we live in? Well, not in this room necessarily. But if you think of everyone who is trying to make peace in the world, how well are we doing? And how do we create this kind of change? How do we make transformative results?

And I'm kind of implying here that there's some strategies and practices from outside our world, outside of the academic space, outside of even programmatic space, maybe even from other countries. Maybe other cultures have figured out other things that we haven't figured out that we could learn from.

And then this is a real concept I'm bringing up, which is the productization of peace. What I mean by that is if I have an idea of I can make an iPhone or something like that. One day it sits in the academic space. But at one point, people have to receive it. So how do we bring it to people that need it? We have to send something someplace to bring peace to folks.

So I want to bring somebody into the room in a second. But I believe one compromise of peace is the sudden exposure to traumatic incidents. Even like if I was driving doing-- I was in a car accident once. That compromised my peace. I'm driving along listening to my favorite song. Black ice, I spin. Time slows down for me. And I remember the technique of riding the car. And I do that for a minute. And then two minutes later, I have this flush over my body and my life is different for a while.

Also one time I gave a presentation like this and took a break. It was an all day presentation. I took a break to go to meet someone to talk about a child who was committing suicide, or attempting. And we were in the car for a total of 20 minutes, which included getting ribs from a Rib Shack.

And we parked our car. And we're eating and we're talking, calling the mom. And we drove away, total elapsed time is 20 minutes. And four car-lengths after we drove away, five police cars. People come out-- long guns, short guns on either side. And I activate a different voice than this, making sure they don't think I'm some other kind of person. I'm just pretending.

We change the way we-- a lot of black men have this protocol to survive this moment. And they said that they thought that we were doing heroin. That was the reason to stop the car. The driver was a white woman. And she said, every time I'm with a black man this happens. And I can call the police commissioner and those types of things.

And I'm, like, here I am having this experience. And then I come back to the room and say, hey, let's continue talking about this stuff. And that's the duality I think some of us have. Is it making sense? I can keep going?

AUDIENCE: Yes.

COURTNEY GREY: So many things compromise our peace. And I actually say to an unsustainable degree, no humans can really sustain this and still be humans. So I'll give you an example. One year, just a penetrating injury alone in a city in America, there were 50 homicides. That's 50 times family and community members got notification that someone was shot. There might be tears. There might be rushing to the hospital.

But in the same year, there, were 500 shootings and stabbings. If 10 people loved those people and were affected by it, that's 5,000 people in one year that had some kind of sudden shock. And if you study traumatic exposure, those shocks and the impact of them don't go away immediately.

In that same year though, there were 32 trauma-inducing crimes-- 32,000. And what I mean by that is home invasions, sexual assault, all kinds of things. All of these induce a trauma, all in a very small, geographic area. The footprint is very small. You can drive from end to end in 30 minutes maximum. Maybe 90,000 people live in that area completely.

So these are all sudden shocks. And some neighborhoods have higher propensities for this and some don't. And some folks might think-- well, wherever there is violence occurring, because they're bad people, they deserve it. They're co-creating that reality themselves. And others might say, people with institutional influence and power and policy-level-change power are not using that access fairly.

Can you just raise your hand if you agree that that's possible what I just said? People with access and power are not using it fairly. OK, good. Because if I start to go off the rails, you have to stop me. If I star to not make sense, you have to say-- wait, wait, wait. This doesn't make sense. And I will see that.

Now, here's the part you have to brace yourself for. I'm going to bring a young man in the room from the study. I only show this one. And I used to play the audio. But I don't do it anymore because there's a slight chance somebody might recognize the voice. So this guy is not named Clifford. But he was 18 years old and he was shot multiple times.

And this is where we're talking to him. He's recounting the second-floor apartment where the police and the EMTs came. And so I'm not going to try to pretend to act him out. I'm just going to-- but I'm and a good actor, people say. So he says, oh, man. It was rough making it here. The cops came into the house. They said, who shot you? Who shot you? And I'm like, I don't know.

"Who shot you? Who shot you?" I don't know. They just put me on a stretcher. They took me down two flights of stairs. They put me in the ambulance. Then they came on to the ambulance. Now he's much more distressed than me on the audio tape.

Then they put me on the ambulance and said it again, "Clifford, you got shot six times, man. You're not going to make it. You're going to die. Who shot you? You shot you?" And he's sitting here saying it. And I know I've been shot six times and I'm starting to believe it myself. And I don't think I'm going to make it either.

So I'm like-- I won't say this word here, because we're in sacred space. So he's like, "Who shot you? Who shot you, man?" I do not know. Hey, come on, man. I'm not going to make it. I do not know who shot me. Very distressed in the voice. I'm sitting here bleeding to death. Could you take me to the hospital please?

Does anybody have a reaction to hearing that, or any analysis? This is-- I think I must have 900 hours of this stuff. Anybody have an analysis, especially a young person that knows anybody who's had anything like this before. This is the interactive part. Does it bring up anything for you hearing this?

AUDIENCE: It brings up Freddie Gray.

COURTNEY GREY: Freddie Gray?

AUDIENCE: He was just detained for a long time And needed to be taken to the hospital.

COURTNEY GREY: Anyone else get a feeling from that, a sensation, or a notion? I think we need to get three out of this audience.

AUDIENCE: I'm not talking about a personal experience. But I'm guessing the police believe that the person knew and wasn't going to say-- that there's a lot of people that don't snitch kind of thing. That must have been what was going on because why else would they be doing that?

AUDIENCE: But he's devalued because his life was--

COURTNEY GREY: Devalued.

AUDIENCE: It's more important for them to carry out the bureaucratic thing of identifying the perpetrator than to save his life.

COURTNEY GREY: Was there another one of you?

AUDIENCE: I think this is an example local authority not using its power correctly because they're more concerned about maybe finding who the culprit is as opposed to the humanity of what's going on here-- so justice versus mercy. Basically they're missing the point.

AUDIENCE: There is a complete disregard for Clifford's well-being. And it appears that there is more of a concern of ticking the box and getting the numbers or the statistics down on paper, than there is for helping this man save his own life. At least, at minimum, help him save his life versus you telling him that, oh, you're not going to make it. So there's a lot of coercion going on in this moment.

COURTNEY GREY: So I'll just give you what I think is going on. Yes, clearly an official in a uniform, who's probably trained in a lot of things, is telling someone there might be something going on with you. You have holes in your body. But all I'm interested in is chasing the other person.

There are times when, if you're in a mass-shooting, where that is necessary. They're not going to stop and take care of the people that are injured. They're going to finding active killer in a scene. But when you're in a scene here like this, you're devaluing me. And everybody in my neighborhood has had experiences since 1950-- you look at Chicago and all the violence that they have there.

If you go back to 1970, there were horrible, horrible things where I grew up in Philadelphia. There was a mayor who used to be our police chief named Frank Rizzo. In certain spaces when I say this name, everybody goes-- whoa, you survived Frank Rizzo? And I lost lots of friends. 14 years old, 13 years old-- wow, they just came here out of nowhere grabbing my friends. And we find out that he's dead later on.

But what I want to get here is, you're going to give a guy the uniform that says this to you, you're likely to just die right there. So you're going to start to believe you could die. And I just want to contrast that with a car accident. Because all these are examples I've done. A car accident in a middle-class neighborhood. And a White boy was hit by a car and police show up.

And they say-- this guy's name is not Johnny. But they say, "Johnny don't die on me. You're going to make it." Is there a difference in someone's ability to survive based on that response? Because if what you're saying is true, then we're talking about something that in my Indigenous behavior or identity, we call God. We call that spirituality.

If I can say a word to you and it's going to change your life and ability to survive injury, there's something going on that we can't just map out on a chart and put an equation on this that's affecting someone's ability to survive. Then compound that with, I train police. I train EMS and so forth. I get trained with them. And I can't imagine someone knowing whether or not somebody was actually going to die by saying those words. I don't know how they discern or ascertain that.

And clearly they were wrong because Clifford is talking to me later on. So they were wrong. So it might affect this person's ability. Did I rob them from the spiritual energy that's required to make-- I don't know what-- blood cells change, molecular actions change and I survive. So clearly this is a space.

And again, there are neighborhoods where-- I grew up in a neighborhood where police were-- the police station was maybe nine blocks away. You had a 45-minute response time. We started believing help is not on the way. So we do things ourselves. We take care of ourselves.

There are neighborhoods in America, modern cities, where response time to pick up someone and deliver them to a place of care is 45 minutes. The odds of survival go up exponentially. In Boston, I think it's maybe 12 minutes to get to a level one trauma center where they can really address the issues.

So to me that's the individual level. And then on top of that, we have the compounds that but I'm just saying, is that there are tribes in America. I speak Portuguese 30% of my time outside of the office. I think I'm more wired as Jamaican than American. I have a Somalian colleague that could be in his room, and you would think he was a Black American. Yet, his cultural practices are very different. His views on the world are very different.

We've had to change policies for treating patients in hospitals because certain of culture of people say, well, the doctor is not around to talk to the woman that's sick. The doctor is not allowed to talk to the children that's sick. He has to talk to our spiritual leader, and the father has to be there as well. And matter of fact, the room is not big enough, because the whole family has to be there.

And I remember being in a hospital saying, OK, we have to restructure the care of this population. A special thing gets done so that we can care for them. And we're very-- we're wired very much differently. And I wish we had enough time together-- because, again, 45 minutes. But there are a few video clips I can show, where you really see the difference.

But just go to another country, like Brazil. Very many people of my same bloodline are there, and they are very different than we are. They view the world very differently. Less individualistic, for example. There's a person in the 1500s that had researched an African culture, learned their language, and wrote to his colleagues, I will never understand these people, even though I speak their language.

They seem not to have a word for individual possessions. I don't know who owns words. It seems like the same word for God, nature, and you and me is the same word. I don't understand that.

They have a concept called Bantu in South African-- Bantu cultures, South African culture. In America you say, oh, that means I am because we are. It's a gross understatement, or simplification of what the word means. It actually means we are almost like a beehive, or something.

We together are one being. That's why nobody's ever homeless-- because a grandfather is a title, not a biological marker. So a grandfather is a grandfather for all the children. A father's for all the children. And our justice system was different then, too, because we know we are one. So if someone harms our communities it's because they're sick. So we heal them and bring them back into the community.

And if you study Foucault and the ideology and intent behind our penal system, it's very much not the case across the board. But we do have friends in prison reform. Our young people advocate for prison reform for a long time. And other countries have it different.

I know of a prison where there's no walls-- a prison in another country where there are no walls. So people stay there willingly, and they have dinner with their families-- because the place is so poor that they're fed by their family while they're in prison. So I'm fed with my family.

And the guards are so poor that the guards and the prisoners and the families eat together every day. And the odds of bringing someone back into the world is faster. Now, in Boston, there was a time when there were 3,000 people given release from prison per year. Most of them could walk home from where they were being released.

So two or three neighborhoods are getting 3,000 humans that had been inside for maybe five, 10 years. That human river cannot be denied. 3,000 yoga instructors, 3,000 people 10 feet tall, 3,000 baseball players, 3,000 teachers-- any human mass of that sort is going to be a hard thing to avoid.

So you get where I'm trying to go? I'm trying to paint a world that is very close by, for which we say the peacemaking is going to make a difference, in terms of how well are we equipped for that. And I think I'm going to skip some of these. I get very excited when I see these things, because I went to I went to a school down the street and these were here all the time. So I'm just going to raise it now. I went to this place called MIT, and they had these boards.

[LAUGHTER]

So I guess the first place I want to say is there's a little bit of sort of, like, where do we pull from from our expertise? And I doubt it's going to be within our own industry. So very few industries that have transformed and made something better got that innovation from its own knowledge base. You reach outside.

So for example, if I was thinking if I thought of peacemaking as delivering antiretroviral drugs for HIV, there was a time when it was just theory. People talked about it in rooms. They were trying to figure it out. But at one point, someone made a thing that's going to make somebody's life better. And they delivered it. Does it make sense?

So who's good at making peace? Where are the experts that we put in the room and say, OK, great, we're not going to get on a plane and bungee jump, or get helicopter dropped-off to someplace that has no peace. And we're clear that predictably and repeatedly we can go to this place and make peace.

Anybody know of a place like that? Anybody know of a team of people that can do that? And is that challenging to explore this notion? Say yes or no, please. It's too challenging to talk about this, or is it OK?

AUDIENCE: It's okay.

COURTNEY GREY: All right. Because it's OK to say, as an industry or as an ecosystem, maybe peacemaking isn't going too well. For example, since Sandy Hook incident, there have been 190,000 homicides. 190,000. Forget that thing I showed about Boston. 190,000 homicides of compromise of peace.

So how do we deliver, and where do we get that science from? One might be just a very paradigm that we are all connected. So if somebody gets shot in some other city-- wow, that was bad. And we might go right about our day, like we don't feel like it's connecting to us personally.

There's, I think, sometimes an egoism of human experience in America, as opposed to the Bantu people I just discussed. I have videos here where something happens to a person and the whole community shows up. I see it even in social-mammal cultures. I have a video of water buffalo showing up, and six lions are trying to kill a calf. And all the buffalo take the calf back. And I'm like, well, where's the mom and where's the dad that would directly impact it? You can't tell.

So are we thinking collectively that the experience of these other people we have the luxury of not seeing-- are we taking that into account as we're thinking about peacemaking? At this point in the conversation, I want people to start planning whatever challenges or questions they have of what I'm saying-- including, well, you're so off-base I don't know what you're talking about-- so that the Q&A can be really rich. Because at one point we're just going to walk out of this room-- 8:30 or so, we're going to nibble some food and walk off.

So can we start thinking about what we could do after today to stay connected? And one of them, I actually think Dr. Harris might be quite instrumental in this-- like, how do we convene ourselves to actually be talking about peace on a regular basis? So I'm going to draw something on the board, which I think is an attempt at framing how we might look at peacemaking.

Very simple. Triangles can be remembered easily. There's an individual. And this also matches this socio-ecological model for behavior change. I'm just going to say family and community here, and society.

So maybe we have to think about individuals that have their peace compromised, and then create peace for those individuals and peace for their families. And then scaffold that up to a collection of peaceful people and peaceful families and neighborhoods, to have a peaceful society. And then the challenges I've talked about quite a bit today are where we have this individual challenge, and then what techniques affect that?

And the traumatic experience of these shootings, these stabbings, these suicide attempts-- the reason that 33,000 people are committing suicide a year in this country, the reason that they're, I think, maybe 1,000 deployments of Narcan-- the drug that revives you after a drug overdose. 1,000 times someone went to someone who's lifeless-- very close-- and said, I'm going to revive you. And when they wake-up, they wake-up a certain way.

Each of those exposures create a compromise of the peace. And if they were to happen to me, you would think I was peaceful. What I mean by that is, if you study post-traumatic stress disorder-- like, I've gone to school after being in a car accident in the morning riding my bike.

And I went to school. And my teacher would say, oh, he's peaceful, because my affect is not showing anything. I have numbing as my primary expression of traumatic exposure.

So maybe I'm code-switching right now, to figure out this notion of being functional here. And even if I don't even know that I'm not doing well, the body also keeps the score. So probably most radical thing I'm going to say here is the absence of peace-- I was trying to create a cool symbol for peace. I'm still working on it. Yeah, peacemaking.

But the absence of peace actually robs people of years of life and debilitates their ability to learn-- those two things. What I mean by that is if you study there's a body, mind, and social interaction. We call the interventions bio-psychosocial.

And it's so extreme that people who are exposed to these things on a regular basis have high propensity to have their children die before the age of one, or a high propensity for them to be born with low birth weight. Or they have their hippocampi-- the part of the brain responsible for long-term memory-- to be reduced in size.

That's what I need to pass standardized tests. It actually happens to us as providers. And the measures that I learned how to serve other people from were designed for our first-responders.

So in order to protect us from what we see in the course of doing our jobs, those interventions were clearly designed to bring the hippocampus size back to normal. So you can recover. That's the good news. You can recover from this.

But if not, the way the hormones change, the way the biology changes, affects life expectancy-- like, 10 years of life. And for some reason, if I stayed in Jamaica with my family, I would die 10 years later than I'm supposed to die here-- if you just study this search.

Now, was that too radical? Anybody believe what I just said? Because we have a very still audience. Oh, look at these people wearing black and yellow. It's kind of hard to know when we have an audience like this. Like, is he crazy? So let me just say, that's the most important. This is the sort of the gravity of why we should get this right.

So that means we can intervene and protect people, also, if we think of a concept of building resilience in people to the things they go through. Can I be taught things that will make me resilient to it? Can I create social connections that make me resilient? So if you study resilience, one of the key factors is social connectedness.

And we have neighbors. We have some neighborhoods where people think that their social capital, their social space is maybe a five-block radius. Like, outside that five blocks, they don't feel safe. They don't feel like they can be protected. And they don't have social connections behind them. It could be because of poverty. A lot of limits today on their ability to live and thrive, I guess.

Now the question is, can we also intervene at the family level? Can we intervene at the societal level, as well? I'm definitely involved in policies. Policies can be laws. But there are also policies for, like, a school. A school can have a policy for how they raise their funds.

And we can say that-- well, we need to raise some money. Let's put vending machines in the building, so we can earn money from the kids buying snacks. And those snacks can have sugar-sweetened beverages and things that will compromise their health. All those things can have healthy snacks. That's like a policy.

I've definitely asked some colleagues-- if you have a White-male and a Black-male boy in first grade, and they're agitated and moving in a room a lot-- raising their hand, jumping up and down, interrupting the teacher. A colleague said to me just this week-- a White-male colleagues said, who's a clinician over multiple schools. I said, what's going to happen if that happens?

Well, he said-- this a White man. He said, if the White boy does that, he's going to get referred to Health Services. If the Black boy does it, what do you think happens? Suspension. But maybe suspension with some aggravation to it-- meaning it could actually lead to arrest. And that arrest ends up on their records, and then it ends up compromising their ability to be employed.

So that's societal-level interventions. And by the way, I should be probably stopping soon, right? I thought we said 7:10. So we keep flowing?

AUDIENCE: [INTERPOSING VOICES]

COURTNEY GREY: Nice. See. Because eventually, I do want to just deliberately stop and say, let's get some kind of dialogue going on here. So at my job, we are constantly trying to address this policy-- for example, the stress of mothers that live in housing developments. We are addressing that. We're changing housing-development policies for what they have access to. And I'm bringing that up because of Dr. Harris's experiences.

We had children that were getting asthma and having a lot of emergency deployments for pickups for asthma. And we actually changed the housing developments to have filtered air. We removed mold exposure. So the environmental things that were causing this behavior-- that's, again, a policy. And when we have willing leadership and willing elected officials are willing people in authority, those things are kind of easy to do.

And frankly, sometimes when we have people who believe that people in despair deserve it and we should be isolated from it, as opposed to it's our duty to show-up. So I'm going to stop soon. I think we need to consider what my improper description of the Samaritan story. We should become uber Samaritans.

What I mean by that is-- I might get this all wrong. Correct me when you get up here. The Samaritan helped a Levite. He helped a person from a place where I believe they were not considered cool people.

Like, even if you were caught helping them, they be like, oh, he's one of those people. And other people would avoid it. Helpers, I would say-- people who were assigned helpers, people who were assigned the power were, like, passing by.

And then this person, who had very little, said, I'm going to show-up for this person-- this person that I don't know, may never see again. And the part of me that can offer something to someone else, that's what I offer. Because I've been isolated.

That experience that I showed on the board where I read the boy's testimony, I lived isolated from that. After coming to college, I didn't see that at all. And I could live a life with the luxury and the privilege of not understanding what it's like to have those shocks.

It wasn't till I worked in housing developments particularly Bromley-Heath in Boston, Orchard Gardens, where people were saying, we are figuring out a way to survive and still be strong and harvest our assets, while living in this madness, basically. So now the question is-- and a good friend that was part of Ferguson. Last time I was with him, it was here on Harvard's campus. His name is Tef Poe. It stands for Teflon poet.

He said-- and I'm going to end on this. He'll be the last person I bring in the room. He said, I used to think it was cool-- that if I sat and watched TV and saw somebody do something bad to a gay guy, that if I said to myself internally, that's wrong, that that made me the good guy. He said, no longer.

In fact, more gay, White men helped me than middle-class Blacks, to get through Mike Brown's experience in Ferguson. So I'm showing up for them now. And he showed a picture of many of them and said, yep, that's my guy right there. I show-up for him. He says, yeah, I can't just show-up for the egoism of my own catchman area, my own scope of concern. It's societal.

I know EMTs that have showed-up to a house to take care of someone. And that person had shot one of their colleagues in the past. And I'll just say it this way. Sometimes God is not watching. I mean, the only person watching is God. The only thing watching you is God.

And it's like, so do I help the person? Do I let them suffer a little bit more? Do I decide I'm not going to do anything, because I'm mad, I don't like the person? Or do you access that deeper part of yourself and push it forth, even when you think you have little? And everybody who's taught me, they come from that breed.

You have to show-up. The natives that I think are from this bloodline, they're friends of mine that are like that. They said, I don't care what you're talking about. You have to show-up.

And unfortunately, because these people in the Black and yellow, I feel bad for them. Because they know me, and they hang-out with me. So everyone here has showed-up for someone they didn't know that was going through a horrible thing. Sometimes people come directly to our place, which is housed in a city school. And they're like, this thing just happened. In Central Square, there was a shooting right next to the Enterprise Rent-A-Car.

And next day, that family was in the place where we're seeing those songs. And they're like, yeah, we need some help. And we do a thing. Some of the stuff we train for-- the work I do. And others are compassionate presence that come from our indigenous identity-- and things that we kind of knew before we got colonized.

The work we do is kind of based on the premise that Black people and people of color-- or African descendents, at least-- knew some stuff before we met colonizers. We lost a lot of it. And this art form that you saw today, which I should tell you is called Capoeira Angola, it's probably one of the best examples of preservation of an African practice and ideology in either of the Americas. 200 cities of escaped slaves-- one of them that never got recaptured until after the abolition of slavery.

White slave owners were saying, let's not recapture them, because they're like another country to us and we trade with them. It's a very powerful success story about organizing and activism. But they also had techniques for healing. And luckily, my work, which is disaster behavioral health, allows for these indigenous practices, so that we can tune it to serving Vietnamese or Bosnian, Cape Verdean, Somalian.

So I think there's a cool thing that's going to happen before question and answer. But I think I should stop there. And thank you for the time.

[APPLAUSE]

SPEAKER 2: Well, good evening. So a couple of things. One, I think I took you a little too seriously. And I sat and I listened the whole time, and I didn't think about anything I was going to say.

[LAUGHTER]

That's the truth. So I listened. I absorbed a lot-- reflecting on it. I am going to say, however, that I'm here tonight-- I'm grieving terribly. So I'm just going to be honest with you. I I lost a very near, dear, and beloved friend recently. And I just went to her funeral on Tuesday.

And it might seem random. I hope it's not. But I'm going to tell you a little bit about her. Her name was Lillie A. Estes. She was 59. And Lillie A., as I called her, called herself a community strategist. She had a college degree, and she had worked.

But for the last 12 years, she lived in public housing. 10 years ago her son was murdered. The person who killed her son was arrested, went to trial, and got off-- and moved back into the same housing development.

Lillie A. Saw this young man all the time. But I came to know her and love her and appreciate her because she was an unbelievable community organizer. So Lillie A. did everything. Anybody who needed anything in the community would go to Lillie A.

And the circumstances of her death, I think, are telling, and speak to some of what we're thinking about here today. And I want to share-- I said she was 59 years old. The average lifespan in the neighborhood where she lived was 63. Four-miles away, in a White neighborhood, the average lifespan was 75.

Now, Lillie was found-- as it turns out, I hadn't heard from her for a long time. And through a certain set of circumstances, I called somebody I knew down in Richmond, who went. And they had to call the police.

It turns out Lillie had been dead for two days. Lillie had been dead for two days, and she was found in her bathtub, fully-clothed. And I just can't think about my friend who had to be there for that.

But here's the point They took Lillie A. They took her out. They took her to the medical examiner, released her to her son, to a funeral home. And they just decided that she had had a heart attack. They didn't do an autopsy. They didn't try to figure out. They didn't investigate. Woman dies in her bathtub fully-clothed, and that doesn't raise an eyebrow worth investigating?

I know we're here in a posture of peacemaking and trying to understand. But as far as I'm concerned that story-- that very reality reproduces itself all over the country on a regular basis-- and that kind of inequity.

So I'm sharing that with you just because-- because I was listening, and I wasn't thinking about what I was going to say when I talked. But there is a connection. Because the work that I did with Lillie Estes, and the way that she and I became friends, was that we had this project called Community Justice.

And Community Justice was based on the notion and the idea that people in our communities-- in the communities that have been, in fact, ravaged by decades of internal warfare wrought on those communities under the terms, war on crime, war on drugs, war in our city, war on people of color, that those communities deserved a different kind of justice. They deserved a different kind of justice than what we call criminal justice, which is what we generally think of.

And so when we chatted earlier I said, I have this idea that justice means being made whole-- being made whole-- and that that kind of justice and that conception of justice applies to individuals who have suffered, experienced harm-- to neighborhoods, to societies, to us as a whole. That something has happened such that we've been separated in some way. We've been harmed.

And Lillie, who was a consummate community organizer-- and the premise of our work is that there are people in all of our communities, like Lillie, who do this work-- like Courtney-- who do this work to make us whole. And that that's what it's going to take to rebuild our society. That's what it's going to take.

When other people talk about criminal justice-- I don't use the term criminal justice. Criminal justice triggers this association between race and criminality. You might not believe it, but I think it's true. So we talk about safety and healing.

In our organization, what other people refer to as criminal justice, we call safety and healing. Because we think that in a community that's what people think about. That's what they're concerned about-- safety and healing. Again, I could listen for quite a bit little longer.

And so I throw this out-- this issue, this kind of question of justice as being made whole. This question of community justice, meaning that we need to make our communities whole as well. And that the way to do that is to rely upon and trigger the voices of people in those communities who know and understand problems, and know and can identify and understand solutions. And that's the kind of language that I think of.

And I'm trying to figure out a way that we can kind of think about that in terms of peacemaking. I don't think of it as peacemaking. But that after I listen to you, I realize that maybe that's what I'm talking about. So I just throw that out to you.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. Thank you.

COURTNEY GREY: Well, one thing that comes to mind is-- we got together yesterday, actually, with Britney. We came to see if our singing needed amplification for this room-- just technical stuff. But I think that it was just quickly up there, that slide that identity shows-- because there was so much animation. But are we believing that peace is the absence of war? So if there's no combatants, nobody's fighting, then there's peace?

And I remember being at the UN and saying, so we're saying that after the war is stopped somebody who's a double amputee has peace immediately? Or don't we have to do a thing for that person to get them whole again? Or within 190,000 families, that father who might have passed away is no longer there to raise the son.

Maybe he earned income. Maybe he drove people to school and to work. That's gone instantly, by the way. It's not like chronic disease, where it took time. Modern society created quick ways to kill people. So it's like something was happening and now they're gone, and instantly your life has changed.

So the fact that nobody is shooting anymore-- maybe you put the guy in jail that did it. And now there's a loss there. And it's a loss across multiple phases. If the person was making $50,000 a year, and they died 10 years ago earlier than normal, that's a significant amount of financial contributions to the home, as we investigate why people are poor. Because they didn't value education enough to go to Harvard.

They just didn't care enough. They didn't try hard enough. But again, the mass of 190,000, just in that small period of time, means that's a lot of making-whole that is required.

And I think, again, there's a disparity in who we decide deserves it and who's willing to go do it-- who's willing to show-up for someone to say, I'm not going to do this today. Like, I have a favorite TV show I want to watch tonight. I'm excited about it. And often I'm not watching that show because a hospital went code black last night.

That means they can't take any patients. That means that there are people in ambulances-- maybe even people in delivery, they're not going to go to that hospital. We have to divert people.

So people are up scrambling, making phone calls. Most people don't know what's happening. Wake-up tomorrow, go to work like it's nothing. But some of us are like, yes, I'm watching the line. If that happens, a pager goes off. Hopefully, I'm not in the city school trying to work with kids, or whatever.

And if I miss it and I'm five minutes late to return that call, I'm kicking myself. Like, I better call immediately. And I'll never see those people who were in those in those ambulances. I'm never going to see the people that were working that night.

Now, not everybody has to do that. And I do have to say something about the tone of what I was saying earlier today. You might not see it on my face. But whatever I said about all the gloom and doom and all that suffering and the compromised peace, this thing called faith, and some other things, have me 100% hopeful about possibilities.

It would take a lot to kill that and me and the people that I'm around. So you can talk about the bad thing and still say, faith and everything-- the data in front of me does not matter. I believe in this thing that's way out there-- the unseen thing. Frankly, I don't think you can do this without that.

SPEAKER 3: A spiritual source. Well, all right. In listening to the both of you, I want to just uphold a couple of things before-- just to give you a heads-up. In just a moment, I'm going to invite you to turn to your neighbor and kind of share what you're thinking, before we have an open question-and-answer period.

But just in brief, I want to thank you for bringing Lillie into the room. Her voice needed to be heard. And if you hadn't spoken of her, we wouldn't have heard her voice. And just think it was kind of a sacred moment, to listen both to her life and let her life speak, but also her death. We need to hear.

And I thank you for bringing Clifford's voice. I know that's not his name, but Clifford's voice into the room, and many others as well. But as I was listening to you, I noticed a passion that I'm going to say I think you both share is finding resources and building a bridge and bringing those resources where those resources are most needed.

And you're looking at very radically different resources-- recognizing that part of the problem is that people are not paying attention to some of the riches that ancestors have passed along, interrupted by colonization. But if we can just access those resources, maybe we can rebuild community. Maybe we can help people become whole again.

I started us off by saying that I think the most radical thing we can do as leaders is to listen. You've reminded us of the power of listening, and also the challenge of listening. Several times I heard you say, I'm not sure how to read this audience. I think I can read this audience, that they were listening.

And what you had to say was so powerful that perhaps some of the silence was about sort of thinking and taking-in some of that. So I'm going to invite you to share with each other. We're only going to give you about five minutes. It doesn't have to be you know one person and one person, but very small groups.

And if you would, talk with your neighbors about what kind of surfaced for you, and maybe some of the things that you want to be sure we engage in further conversation. And then I'll interrupt you just about when you get started in an interesting conversation and bring us back together.

And that's when we'll have a sort of large-group conversation. All right, ready? All right, introduce yourselves. Get to know somebody next to you.

SPEAKER 4: Thank you. I have more often been in your shoes right now than in this shoe. And I remember how it feels when the moderator says you've got to come back. I never liked that. But thank you.

We have a clarifying point, we were kind of discussing up here. And so I want to just give a moment to our discussant to share a very, very keen and important insight. Go right ahead.

SPEAKER 2: So I just wanted to clarify what Emily said. I think I have this kind of notion and critique of Harvard's notion of leadership. And I just want to make sure that we understand that when this kind of question of taking resources to a community, or whatever, that that's our responsibility-- that we need to be clear that that's not our responsibility, right? That we don't take things and deliver them, right?

And that in fact, we do what we try to do here today, and what Courtney talked about, is that we listen. And we recognize that communities have resources. It's not the absence of resources. And that we at Harvard can be in a position to be involved and engaged in some ways, but that the real leadership-- the real ability to lead is to follow and is to allow others to lead.

And I'll tell you, in my work, I work with a lot of non-profits and people who do a lot of community stuff. And it's the hardest thing in the world for professional helpers to do, is to not immediately step-up and lead. So anyway, I just wanted us to kind of sit with that and hold that for a while.

COURTNEY GREY: All right. I'm going to build on that a little bit. So in the field of racial justice and all kind of healing work, I end up in rooms where people have access. I used to think it's because my name was Courtney, and they think I'm a woman till they actually see me in a room. And then they're like, ahh. And I'm like, ahh. And then I have to do trauma work to put them back together.

But in the room, you'll hear them say, well, and because we have the community here, we have the community's voice in here. And I raise my hand. I go, wait, wait. Because David and I are here, you say you have the community here? I said, no, no. This is Shirley Chisholm. She said, there's no such thing as a leading Black. There's just Blacks in the lead. Because White people with power know my name, I ended-up in his room.

But if you think I'm speaking for the community, please stop. Let's get in our car. We can drive. It takes only 12 minutes to get to Mission Hill right now from here. 20 mins you're in Bromley-Heath. And we can go there right now. And we'll be in front of tons of the community, whose voices you normally don't listen to. And when they say, ouch, the wrong way to something we're doing that harms them, you will call them an angry Black woman, or an angry Black man-- they're belligerent-- and give yourself permission to not listen anymore.

And I do think it's beyond listening. Though the neighborhoods I've gone into, I've definitely gone in thinking, wow, I've got this great thing you need. I do trauma response after homicide. And they said, OK, so where have you been for the last 50 years, and who's teaching whom? Because we were doing this for 50 years without you. And I said, wait, let me go back. We went back to the laboratory and said, wait, wait, we have to make some changes.

And our attitude is the equivalent to we made a guitar, can we come to the community and-- we're going to give you the guitar, if you want it. And you play your own music. It has some structure to it, but you're going to play your own music. But we're not here dictating what you do.

And I've definitely been in rooms where people assumed that there was not wisdom in the room. And then people said, oh, PhD, deputy director, bureau director, who told you thought you could come just here and just do this? But those are only communities that fought for their power.

I've seen others that have gotten pummeled. We can do whatever we want. You have no ability to stop it. And if something went wrong, we won't even see it, but we can brag about it and get further funding and perpetuate our practice. And that scares me.

SPEAKER 3: I'm going to start asking some of the questions that have been written. But we have a couple of mics. We'll come out. You don't have to write it down first. But I'm going to start with one of these.

And a part of what we're doing tonight is paying attention to the impact of long-term, sustained experiences of trauma. So this person asks, "If you've grown up in a household always full of trauma, how do you know what peace is, when trauma is your everyday normal?" Either one of you.

COURTNEY GREY: OK. So there is an intersection between peace and healing from trauma, but they're not the same. So often I say, you can't establish peace if the healing from the bad thing has not been delivered and sustained-- and that people in that resilant afterwards. Resilient meaning, like a branch. I can bend this branch. And when I release it, it can go back to normal. And that's a very rudimentary belief.

I used to think that resilience really meant, oh, those guys are strong. So when something bad happens to them, we don't have to do anything. And I used to hate this word. But we're trying to redefine it. Eventually, we will not use the word resilience anymore.

But if you know nature, you could bend that branch so much that it will grow bent. And it will not just come back at all. And there's also a weight that will break it. So some people are subjected to things-- for example, our prison population-- that is hard to bring people back from. We did we train people to be killers and send them off to war, and we don't do we equal and opposite when they come back.

Natives would say, if we train this guy-- there are tribes in Africa where they train people how to defend against lions, for example. They're not scared. They're like, we have a system. But when we train someone to do that, there's a time when we take them off and we do some things to make them whole again. They actually consider it that they're not human for that moment. And like, you got transformed to something inhuman, and we bring you back.

So there are definitely things that are like, this is beyond what we can do. And I think systemic things are going on. There's a report called "1.5 Million Missing Black Men," from the New York Times-- or at least they wrote about it last. Basically, it says, improper incarceration, and maybe justified incarceration and early death, means that at birth there's some equal amount of Black men and women when they're born. And by a certain age-- middle-aged or so-- there's 1.5 million fewer men than women in the Black race, because of these unfair and preventable things.

Now, that means as a societal level, I don't think that we can just say there's a time that you can guarantee that that suffering is gone. It's almost like a hazard. Like, I want to put a vaccine around people, so they can sustain being in this hazardous space. But sometimes if a hazard came into this room-- like an airborne hazard-- we'd have to remove you from the room.

And frankly, sometimes removing somebody from a traumatic space means only driving 10-minutes away and being in another zip code-- a zip code that I've walked in before and been pulled over by police because I was walking there. And like, what are you doing here? I'm like, do you do that to everybody that comes by? So they're safe places. And safe places are for certain populations, and places where suffering happened.

So every level of this, I believe, the household where the question came from, and the neighborhood as well, that there are some things that are beyond us.

SPEAKER 3: Well, you go first.

SPEAKER 4: I was just going to say, I wondered if you could say a word about the music, and how does that convey, create, establish-- I don't know what you would want to say, peace amongst people who are experiencing?

COURTNEY GREY: So some cultures-- I've been studying death rituals from different countries. And not everybody believes that there's unrecoverable suffering after a bad thing. So in some cultures, there's call-and-response singing, within in the same day that you found out your colleague died.

And the neurological research we had to do to invent the techniques that 9/11-- so it's a lot to say here. But when 9/11 happened, it upgraded the mental-health system, but most people had never seen these techniques. But those techniques allow for what they call bio-psychosocial interventions.

So if somebody says mindfulness is good-- I was on a panel for mindfulness-- kind of the same things here. So who gets mindfulness? They come to me and say, some people need it badly, so let's all come together and give it to them. But if you believe yoga is helpful for healing, that means that you believe that there is a neurological impact of putting your body in a certain position or saying certain words, or thinking certain thoughts.

Now, we have neurological research that shows if you breathe a certain way, you will break down the trauma hormones that your reptilian brain makes when you're subjected to a trauma-- adrenaline, cortisols, and probably 25 other things that we haven't learned to study yet. So it's actually good for a society people, if you take a big breath and say area, and the in-breath is much longer than the out-breath. It's been researched to no end.

And often when we do trauma response, and a room like this is full of people that are crying, one way we do that is we kind of trick people-- actually, Lina one time did it at a party where a stabbing happened. She put her hand on a guy that was tripping out. Big as a football player, and she put her hand on his body and manipulated his breathing, such that the in-breath was, like, three seconds and the out-breath was, like, six seconds.

So I'm likening the trauma response to what happens with call-and-respond singing that many indigenous cultures do. So even pictures that you might see in the old caves in France-- very old. It shows a picture of a hunt. And then one of them got speared by the saber-toothed tiger, or the mastodon or something.

And they bring it home and they're like, well, we got food and we're dancing. And even though this ancient person that I call Chuc Ta. Chuc Ta died. And we're having a party right now. And because we do that, we're more resilient as a people and more socially connected.

So you go to a Black church, you go to a Cape Verdean funeral, you see that in the midst of all this bad stuff, there's also this call-and-response singing. I can also tell you things about when you debilitate one part of the brain by making it play a complex rhythm, it opens up other channels of the brain to access other things.

And Africans will say the part that gets opened is the only part that actually talks to God. Not my frontal lobe-- not my emotions. Oh, she's cute, I got to stay with her, even though she's treating me bad. That's the frontal lobe. The part that they say God controls is the same part that controls my body temperature when I go outside.

If I go outside right now, my body will raise temperature to match outside, so I stay at 96.8 degrees. That part gets a chance to connect to God when you debilitate this emotional, frontal lobe stuff.

That's a long conversation. But those two spaces are how I kind of justify call-and-response singing.

SPEAKER 3: Thank you.

DAVID HARRIS: So first of all, the ground rule here, both of you, don't call me Dr. Harris.

COURTNEY GREY: They started off calling me Mr. Grey. I'm going, who are they talking about, Mr. Grey?

SPEAKER 3: I think you're not mic'd. I want people to hear you.

DAVID HARRIS: I think you're talking to my parents, or something.

SPEAKER 3: David.

DAVID HARRIS: David. Thank you. So listen, I'm, I think, the odd duck here, because I think about systems. And I think about structures. How many people have seen a film called The Angry Heart? It's actually a great film. You know this film? About Keats, right. It's about a Boston guy who has a heart attack.

I won't say too much. But he has a heart attack and he survives it. And so it's a film about kind of his journey through faith and recovery and his physical recovery. There is a point in this in the film when he says, you know, before this heart attack, I used to think I was really strong.

He says, I used to think I was like a rock on the shore. And the waves would hit me, and I would still stand, he says-- proudly. He says, what this heart attack has told me, though, is that every time that wave hit me, it took a little piece of me off. It made sand out of me.

So my mind goes to those structures that have us sitting up on that hill-- the circumstances of that life. And when Courtney talks about there's a neighborhood 10 minutes from here, or something, my mind goes to, why is one neighborhood one way and another neighborhood's another way? Those are structures. There are structures that work in our society.

Racism is one of them. Inequality is structured in. And I think it's important for us to kind of answer the question about that individual, but it's also important to answer the question about the structures of society that support that family and support that kind of behavior. And so I think we need to think about the healing of the individual, but we also need to think about changing the structure and working on the structural problems that create some of the violence we face.

SPEAKER 3: Anybody not write one down, but have a question they want to ask?

COURTNEY GREY: There's one there.

AUDIENCE: So I'd like to know how we can generalize this discussion in our social and political interventions, so that we take everybody in. And not just descendants of enslaved people, not just victims of colonialism, but victims of capitalism. They can be all sorts of skin colors, including White. I mean, I don't see how we're going to get out of this if poor people don't unite, regardless of their racial or ethnic identity.

SPEAKER 3: Did either of you want to address it, or would you like me to?

DAVID HARRIS: I have a thought on it. So poverty is the primary structural element. Poverty is what distinguishes on one level the material circumstances of one community from another.

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE]

DAVID HARRIS: Yes. That might be beyond me. But capitalism as a system is by nature dehumanizing. So yes, I think we need to have that as part of our conversation. I'm not sure how it addresses the particular circumstances of the person's family, except we could have a kind of structural analysis that tells us it does. But I want to hear you two talk.

AUDIENCE: [INAUDIBLE]

DAVID HARRIS: Well, I mean, at least. At least.

COURTNEY GREY: So there's this concept called targeted universalism, which basically directs the thing that's needed with equal outcome to whomever needs it. So in a rich affluent suburb of maybe Littleton, Mass, there's a ton of people abusing substances. It's a different outcome.

A number of our friends set-up a system to protect federal employees during the shutdown. And it was not being delivered race specifically. I mean, like a Samaritan protocol. There's a thing and they need it. I don't mean, like, if you stop at a stoplight and somebody has a cup. And they say, hey, do you have anything, and you take the $0.29 in the door of the car that you don't really care about and give it to him. I'm saying, like, you're delivering a real thing.

Those who are wired that way, you deliver it everywhere. We got training in the Lakota Tribe. They were like, you have to find a way to give such that there is zero reward for the giving.

And I think the Jewish culture, where there's multiple forms of giving and not all of them are good. Some of them are considered sins in at least our culture. So no, you have to give it a certain way, where it doesn't have the ego-- I gave the best present at the party, or this person now owes me a little bit. There's so many ways in which we unconsciously give where it's-- it has to be this pure giving. And you practice it all your life.