White, Christian America has represented centuries of cultural, political, and economic domination, says author Robert P. Jones. Yet during the last couple of decades, demographics and culture have shifted dramatically.

Jonathan Beasley/HDS

Worry in white, Christian America

Its recent decline has prompted pushback around the nation, author says

Shortly after the re-election of President Barack Obama in 2012, the conservative Christian Coalition sent an email to its members. It included a photo taken in 1942 of a white Christian family praying at the dinner table, patriarch seated at the head.

The note below the photo read: “We will soon be celebrating the 400th anniversary of the first Thanksgiving and God has still not withheld his blessings upon this nation, although we now richly deserve such condemnation. We have a lot to give thanks for, but we also need to pray to our Heavenly Father and ask Him to protect us from those enemies, outside and within, who want to see America destroyed.”

According to Robert P. Jones, the founder and CEO of Public Religion Research Institute, the note’s “apocalyptic ring” stems from the anxiety, fear, and anger of some conservative white Christians who he says have, in the space of a decade, moved from the mainstream to the minority in America. In a conversation Wednesday evening at Harvard Divinity School with journalist and political analyst E.J. Dionne, Jones laid out the data behind his claims, collected in his recent book “The End of White Christian America.”

Jones characterized white, Christian America as representing centuries of cultural, political, and economic domination. Over the last couple of decades, however, demographics and culture have shifted dramatically.

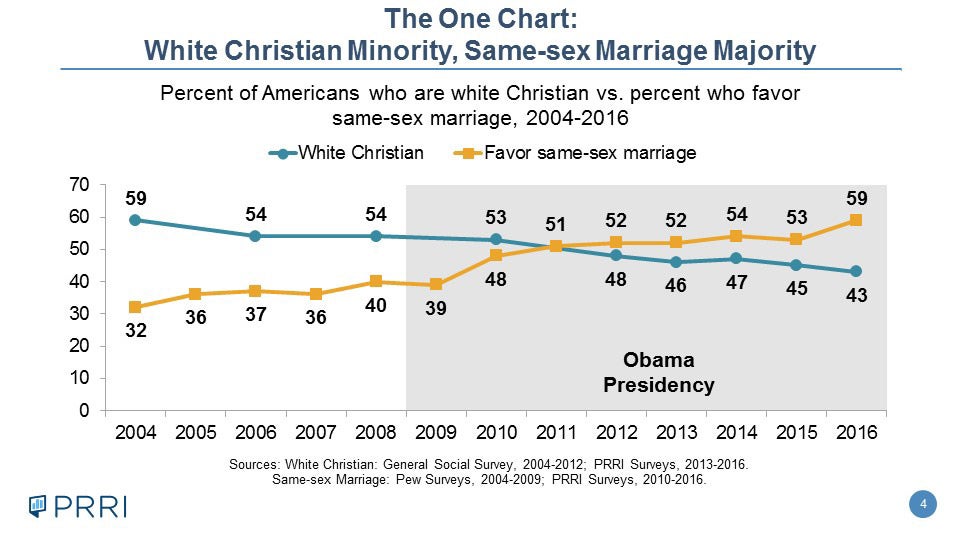

During the years of the Obama presidency, for instance, the percentage of Americans who identified as white and Christian declined from 54 to 43 — more than a percentage point every year. During this time, the United States “crossed from being a majority to a minority white Christian country,” Jones said. At the same time, support for the institution of same-sex marriage rose from 40 to 60 percent of Americans.

“If you are a conservative, white Christian, these numbers constitute a kind of cultural vertigo,” he said. “You’ve gone from being in the mainstream to [an era where that is] no longer true.”

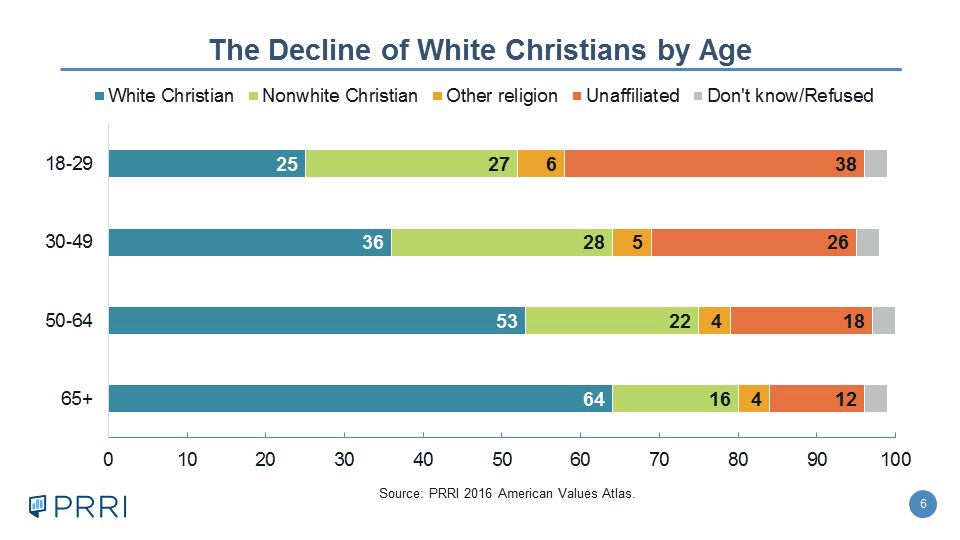

The changes in religious affiliation between generations of Americans are even more striking, Jones said. In 2016, 64 percent of those aged 65 and older identified as both white and Christian. Among 18- to 29-year-olds, the number was only 25 percent. Nearly 40 percent of young Americans claimed no religious affiliation at all.

“What turbocharges the cultural changes is the exodus of young people,” Jones said. “Those kids were raised in churches and left. By all measures, very few of them look like they’re coming back.”

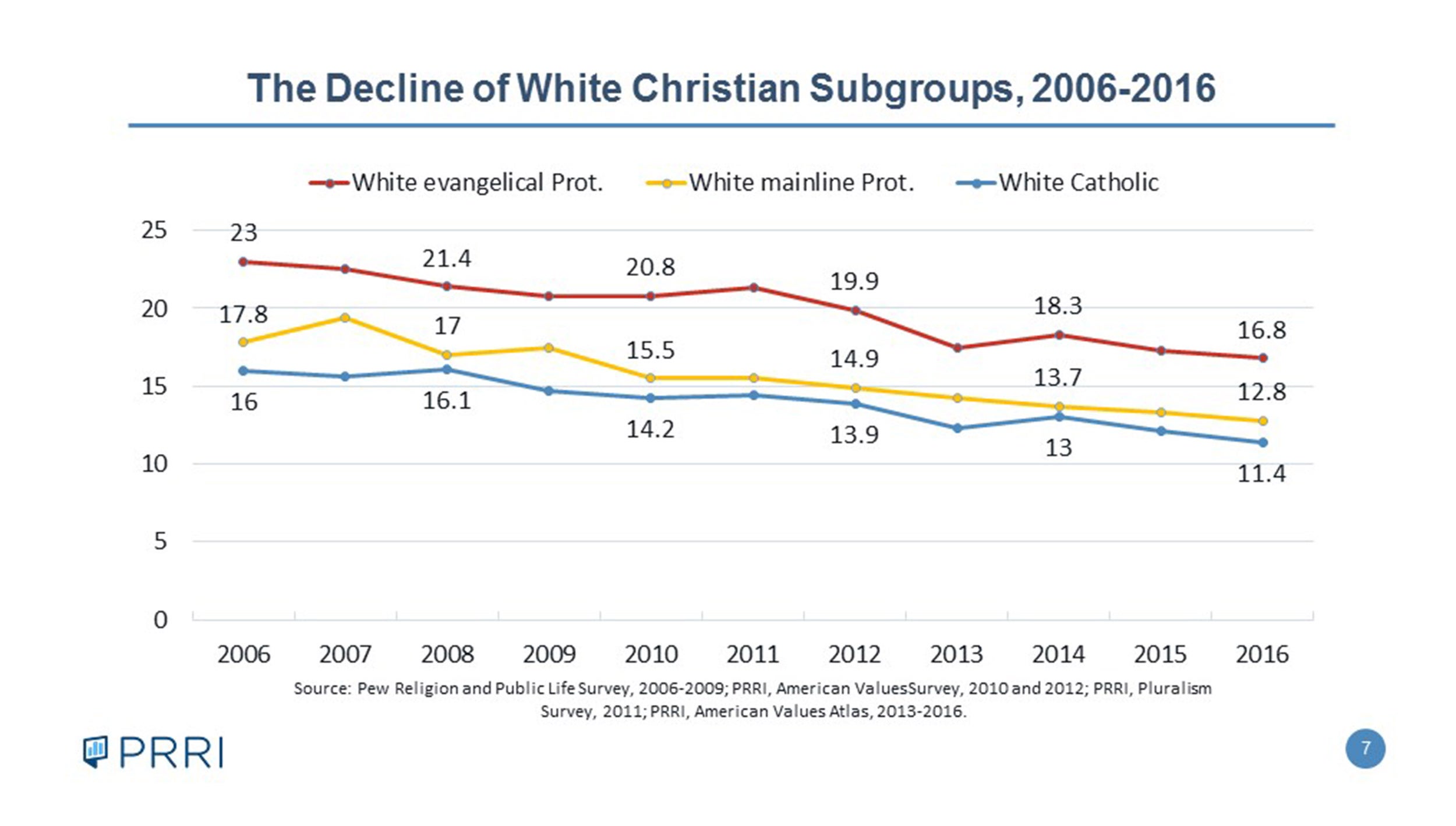

Moreover, conservative churches are now seeing declines that were once limited to progressive Protestant denominations. Jones noted that 23 percent of Americans identified as white evangelicals in 2006. In 2016, that number was only 16 percent.

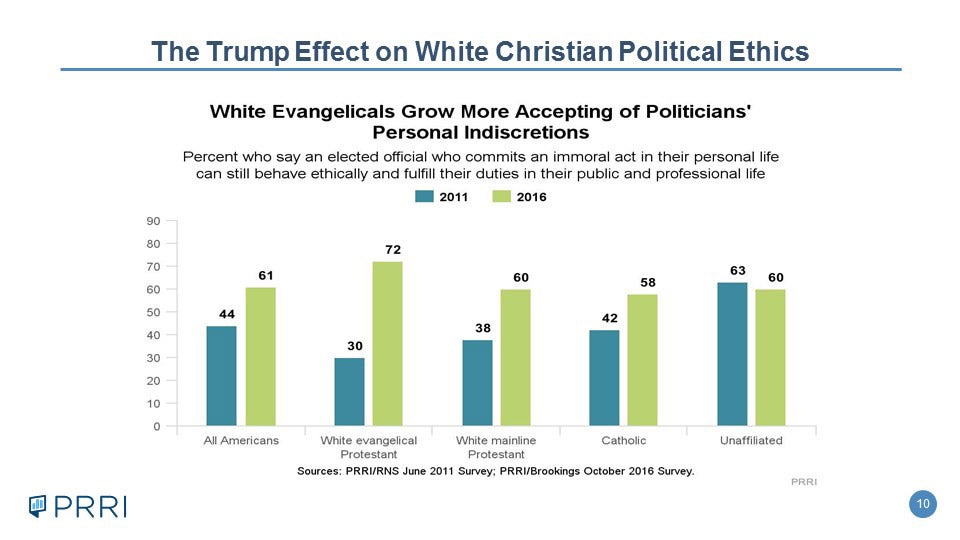

The numbers “explain why it feels like a fight to the death for some in the white, Christian world,” Jones said. They also account for a startling turnaround in the attitudes of so-called “values voters.” In 2011, the institute asked Americans “whether a political leader who committed an immoral act in his or her private life could nonetheless behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public life.” At that time, Jones wrote, “only 30 percent of white evangelical Protestants agreed with this statement.” When the institute asked the question again in 2016, 72 percent of white evangelicals said that they believed “a candidate can build a kind of moral wall between his private and public life.”

The sentiment carried into the November presidential election, when around 80 percent of self-designated white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump — the most weighted support of any American religious constituency.

“Donald Trump got the highest percentage of white evangelical vote since we began recording,” noted Dionne. “Before Trump, the personal life of a politician really mattered. After Trump, it really didn’t matter.”

Both Dionne and Jones characterized the rightward trajectory of white Christians over the past 50 years in large part as a reaction to the gains of the Civil Rights, feminist, and LGBTQ movements, as well as to predictions that the U.S. will for the first time be majority nonwhite by 2042. As a result, the coalitions behind the country’s two major political parties look radically different.

In 2012, “the Obama coalition looked like 30-year-old America,” Jones said. “The Romney coalition looked like 70-year-old America … Ten years ago, the GOP was 80 percent white and Christian. Today that’s 71 percent. We’re on a trajectory where we end up with a white Christian nationalist [GOP] and everyone else.”

Dionne noted that shifting demographics and the rise in religious disaffiliation created coalition management problems for Democrats that may have cost them the White House in 2016.

“There was fear in the Clinton campaign that the young would be turned off [by talk of religion] and that there’s a lot of anger toward conservative Christians whom they see as inimical to who [liberals] are,” he said. “But not to talk to religious people was a mistake. [Methodism] was the most authentic piece of Hillary Clinton. If you want to carry Michigan and Ohio and Pennsylvania, you can’t do it with only a secular coalition.”

Jones and Dionne spoke hours after news broke of the death of “America’s pastor,” the Rev. Billy Graham. Dionne called Graham’s death a “reminder of the era [Jones] writes about [that] in some ways is passing away.” Jones, who grew up a Southern Baptist in Mississippi, worked for Graham during the summer of his senior year in college. He noted that the evangelist refused to hold segregated rallies in the South, counted the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. among his friends, and tried to reach beyond his white audience.

Jones contrasted his approach with that of his son, the Rev. Franklin Graham, and said that the two represented the response of white Christian Americans to two eras, 20th-century ascendancy and 21st-century decline.

With Billy Graham, “There was a deep invitation to become part of Christian life,” he said. “Franklin Graham was public in his support for Trump, critical of Obama and Black Lives Matter, and in lockstep with the Christian right movement. Billy Graham’s death is the passing of an era when evangelical Christianity was more sure-footed — and more sure of itself. Now it’s more defensive.”