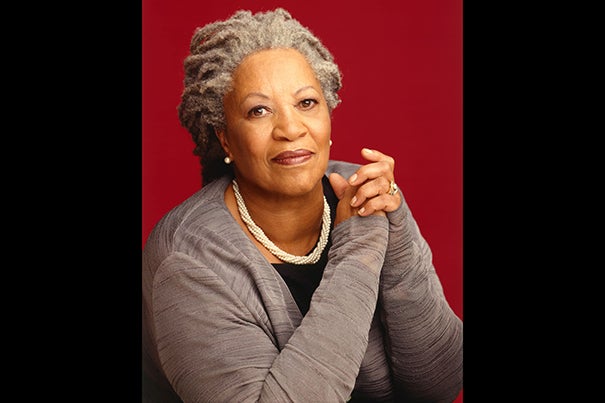

Toni Morrison delivers the Harvard Divinity School’s Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Good, but never simple

Toni Morrison illuminates concepts of virtue, and its opposite

Toni Morrison silenced the audience in Sanders Theatre on Thursday afternoon, not with one of her own stories, but with a tragic tale from real life.

The author, the recipient of the Nobel Prize in literature in 1993, recounted the “mindless horror” of the 2006 murder of five Amish girls in a one-room Pennsylvania schoolhouse by a gunman who then committed suicide, and the shocking reaction to the tragedy. Instead of demanding vengeance, the community comforted the killer’s widow and children.

Their behavior “seemed to me at the time characteristic of genuine goodness, and so I became fascinated, even then, with the term and its definition,” Morrison said. Above all it was the community’s silence, its refusal “to be lionized, televised,” she added, “that caused me to begin to think a little bit differently about goodness as it applies to the work I do.”

Morrison expanded on the theme of goodness for the Harvard Divinity School’s (HDS) 2012 Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality. In a talk titled “Goodness: Altruism and the Literary Imagination,” she explored how authors illuminate concepts of good and evil. She also examined the treatment of goodness in her own novels.

“Expressions of goodness are never trivial in my work, they are never incidental in my writing. In fact, I want them to have life-changing properties and to illuminate decisively the moral questions embedded in the narrative,” she said.

“It was important to me that none of these expressions of goodness be handled as comedy or irony, and they are seldom mute. Allowing goodness its own speech does not annihilate evil, but it does allow me to signify my own understanding of goodness: the acquisition of self-knowledge. A satisfactory or good ending for me is when the protagonist learns something vital and morally insightful and mature that she or he did not know at the beginning.”

A true exploration of goodness demands a thorough examination of its opposite, Morrison argued. The author, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1988, said that she has never “been impressed by evil,” and that she is “confounded by how attractive it is to others and stunned by the attention given to its every whisper, its every shout.”

“Evil has a blockbuster audience,” she said, “goodness lurks backstage.”

With a few notable exceptions, the 19th-century novel made sure goodness triumphed in the end. Writers such as Dickens, Austen, and Hardy mostly held to a formula that left their readers turning the final page “with the sense of the restoration of order and the triumph of virtue.”

But there was a “rapid, stark” shift away from such endings in the wake of World War I, as writers confronted a catastrophe “too wide, too deep to ignore or to distort with a simplistic gesture of goodness.” In Faulkner’s “A Fable,” which tells of trench warfare between German and American forces, “evil grabs the intellectual platform and all of its energy,” said Morrison.

Goodness hasn’t fared well since. Through portrayals of grief, melancholy, missed chances, and personal happiness, authors depict their versions of evil. “It hogs the stage,” said Morrison. “Goodness sits in the audience and watches, assuming it even has a ticket to the show.

“Many of late and early 20th-century heavyweights – Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow, Philip Roth – are masters of exposing the frailties, the pointlessness, and the comedy of goodness,” she added.

But in Morrison’s work virtue is a force, and it takes various forms, including the instinctual form of a mother desperate to save her child. In “A Mercy” (2008), which revolves around slavery in the United States in the late 1600s, one of the main characters gives her child away to a stranger in order to save her.

The mother’s compelling motive, “seems to me quite close to altruism, and most importantly is given language,” said Morrison, “which I hoped would be a profound and literal definition of freedom.”

In the mother’s words, Morrison read: “To be given dominion over another is a hard thing. To wrest, or take dominion over another is a wrong thing. To give dominion of yourself to another is an evil thing.”

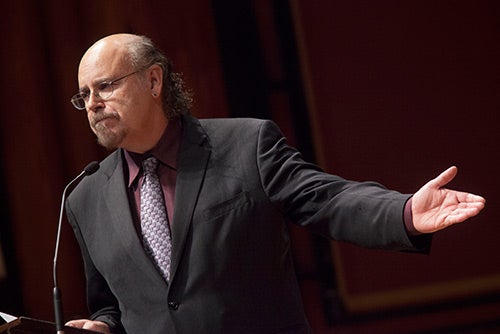

Many in the crowd arrived well prepared. For the past three months, members of the Harvard community have met weekly at HDS to explore the religious dimensions of Morrison’s writings. The working group, convened by David Carrasco, Harvard’s Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America, and Stephanie Paulsell, Houghton Professor of the Practice of Ministry Studies, brought together scholars from across the University.

Earlier Thursday the group met for the final time, with Morrison in attendance. “We are grateful to Toni Morrison for creating this extraordinary body of work,” said Paulsell. “We could swim and swim in it for several more semesters and never reach its depth.”

The guest of honor was ready to engage with an eager group that included avid readers and fans. In response to one question, Morrison expanded on the intersection of the divine and the human. “This is really what art is for … whether it’s music, or writing, or dance … that’s what it does in the best of times.”